Note: This Article is a response to Harlan Yu & David Robinson’s The New Ambiguity of “Open Government"

Introduction

Open government has risen on the international agenda, and as Harlan Yu and David Robinson rightly note, the concept has become “vogue but vague.”[ref]Harlan Yu & David G. Robinson, The New Ambiguity of “Open Government,” 59 UCLA L. Rev. Disc. 178, 205 (2012).[/ref] In the 1970s, NASA and the broader science and technology community created a set of technical standards designed to facilitate access to raw, authoritative, and unprocessed scientific information.[ref]Nat’l Research Council, Earth Observations From Space: The First 50 Years of Scientific Achievements 6 (2008).[/ref] These standards, referred to collectively as open data, burst into public consciousness with the growth of the internet, as demand soared for access to public sector data in formats that facilitate reuse. Open government, by contrast, has its roots in a civic push for greater transparency and accountability in the decades following WWII.[ref]See Alasdair Roberts, Blacked Out: Government Secrecy in the Information Age 14 (2006).[/ref] The movement’s first major victory was President Lyndon Johnson’s signing of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) in 1966, and open government advocates have continued to press for greater transparency and public access across all domains of governmental activity.

The convergence of open government and open data was cemented on the Obama administration’s first day, when the president released a Memorandum on Transparency and Open Government.[ref]Barack Obama, Transparency and Open Government, WhiteHouse.gov, http://www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/TransparencyandOpenGovernment (last visited Oct. 20, 2012).[/ref] The memo committed the administration to “creating an unprecedented level of openness in [g]overnment,” and established transparency, participation, and collaboration as the driving principles of the President’s Open Government Initiative.[ref]Id.[/ref] An Open Government Directive followed soon after with clear guidance to agencies about how they could put these new principles into practice.[ref]Peter R. Orszag, Exec. Office of the President, Memorandum No. M-10-06, Open Government Directive (2009), available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/assets/memoranda_2010/m10-06.pdf.[/ref] The commitments advanced in both documents reflected a new alignment of open source and transparency, as the long-running focus on access to information extended to include the possibilities for transformational political change embodied in open data.[ref]Id.[/ref]

Bringing open data and open government under a single banner, Yu and Robinson argue, leads to conceptual muddling that ultimately holds back progress for both projects. In their view, blurring the “technologies of open data” and the “politics of open government” will lead to frustration and disappointment.[ref]Yu & Robinson, supra note 1, at 181–82.[/ref] They appear especially concerned with the implications of the embrace of open data for progress in the open government movement. The danger is that governments will get credit for increased transparency by adopting open data standards without meaningfully committing to steps that increase accountability. Advocates of open government in the United States consistently raised this concern as they challenged the ambition and performance of President Obama’s Open Government Initiative.[ref]See Joseph Marks, The Truth Behind Transparency, Gov’t Exec. (June 1, 2012), http://www.govexec.com/magazine/features/2012/06/truth-behind-transparency/55989.[/ref] International advocates of greater transparency and accountability, such as Nathaniel Heller at Global Integrity, have echoed this view, worrying aloud that “open data [may provide] an easy way out for some governments to avoid the much harder, and likely more transformative, open government reforms that should probably be higher up on their lists.”[ref]Nathaniel Heller, Is Open Data a Good Idea for the Open Government Partnership?, Global Integrity (Sept. 15, 2011, 12:41 PM), http://globalintegrity.org/blog/open-data-for-ogp.[/ref]

It is difficult to disagree with Yu and Robinson’s narrowest claim. Greater clarity about the complementary but distinct objectives of these different movements—and the likely impact of the specific governmental policies they advocate—is undoubtedly a good thing.

But saying that open data and open government “can exist without the other,”[ref]Yu & Robinson, supra note 1, at 181.[/ref] is not the same as saying that they should. Drawing on our respective experiences as a partner in Kenya’s Open Data effort and as a key architect of President Obama’s multilateral Open Government Partnership, we argue that the growing ties between the open data and open government movements, particularly in developing countries, can benefit both agendas.

We explore this hypothesis in four parts. Part I proposes that open data can be an important precursor to a broader notion of open government. Even if initial data releases are inconsequential for accountability, such releases spark a public conversation about what data matter and contribute to changes in norms and practices inside government. Part II suggests that open government can enhance the civic value of the open data movement, bolstering its relevance by encouraging a focus on technical solutions that improve public services and promote public integrity. Parts III and IV explore these dynamics in the context of two specific efforts: the Kenya Open Data Initiative, Africa’s most prominent project to make public data accessible, and the Open Government Partnership, a multilateral initiative aimed at developing high-level governmental commitments to transparency and accountability.

I. Open Data as a Precursor to Open Government

First, the fact that a commitment to be more open now can be fulfilled in a wider variety of ways may provide an entry point for governments to take concrete steps toward openness, especially in countries where traditional open government advocates confront ingrained resistance to difficult reforms. This could be a worrying development if, in the authors’ words, governments might use open data to “placate the public’s appetite for accountability” with less meaningful gestures.[ref]Id. at 203.[/ref] But consider how this may play out in a practice.

A commitment to open data involves reorienting the production of information in a public bureaucracy. The adaptability that is so prized by open data advocates requires a culture shift for public officials—a recognition that information is more valuable if it is structured, machine readable, and available for interested users to access (or download) in raw formats. Implemented seriously, a commitment to open data necessarily makes bureaucracies more citizen facing and may even begin to change broader norms about openness.

Demands resulting from a commitment to open data may also accelerate cultural changes inside governments. The launch of open data portals in a variety of countries has generated headlines about what data are missing rather than what are made available in the first iteration.[ref]See, e.g., What if . . . : How the Kenyan Government Should Be Using Open Data, iHub Blog (Aug. 12, 2012), http://www.ihub.co.ke/blog/2012/08/what-if-how-the-kenyan-government-should-be-using-open-data.[/ref] This consistent pressure on governments, even from a small, vocal minority of users, can fuel greater steps toward openness and pave the way for bureaucratic entrepreneurs to push the agenda even further. Moreover, open data commitments attract new entrants into political and policy debates around openness. These entrants are usually technologists who were not previously focused on what the government made publically available but who are inclined to think about how the latest consumer technology can help optimize interactions between governments and citizens. These developments on the demand side of open data are already helping to broaden the constituency for transparency well beyond the committed core of activists who have worked on these issues for years. For example, the 2012 calendar of conferences on open government[ref]Alex Howard, 2012 Gov 2.0, Open Government and Open Data Events Calendar, gov20.govfresh (Apr. 13, 2012, 10:56 AM), http://gov20.govfresh.com/2012-gov-2-0-open-government-and-open-data-events-calendar.[/ref] has twenty-nine events listed, including the Personal Democracy Forum, a conference on the internet and politics, featuring 120 speakers ranging from architects to anthropologists, and the International Open Government Data Conference 2012,[ref]2012 International Open Government Data Conference, Data.gov, http://www.data.gov/communities/conference (last visited Oct. 20, 2012).[/ref] an open government event hosted by the World Bank and the U.S. government, drawing attendees from over fifty countries and including chief innovation officers, representatives from startups and open source projects, and traditional transparency advocates and journalists.

Importantly, it is unlikely that resistant governments would implement the most difficult and prized open government reforms if they did not have open data as an outlet. Politicians opposed to greater public disclosure that enhances accountability are resistant for a reason; often, they fear that greater transparency may expose corruption or challenge their legitimacy. These same leaders, however, often have a strong interest in using information and communication technologies to improve government efficiency and in developing a global reputation for innovation. It is therefore possible that open data provides a useful entry point for government openness in a wide variety of environments, including the most restrictive contexts, and that a governmental commitment to modernization, technology, and public access to data can pave the way for deeper and more meaningful open government reforms down the road.

II. Open Data as a Partner to Open Government

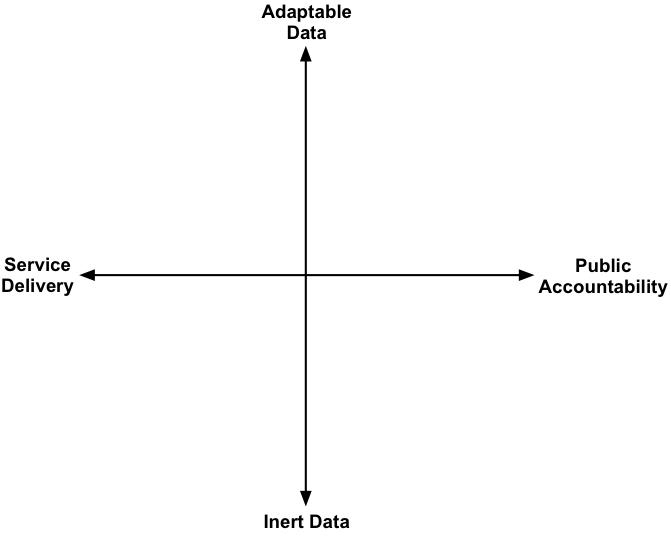

Second, while the open government and open data movement emerged separately, they may be stronger together. To make the point, let’s examine Yu and Robinson’s conceptual diagram.[ref]Yu & Robinson, supra note 1, at 183.[/ref]

In which of the four quadrants would you place the leading advocates of open data and open government? Open data advocates have made their name by focusing on online data releases in politically uncontroversial arenas, the upper-left-hand quadrant. Open government advocates, by contrast, have fought for access to politically sensitive information that gets to the core of how government operates but have been willing to accept that information in formats that make it inert, in other words, the lower-right-hand quadrant. While we agree that data adaptability is important across the board, the collaboration between the open data and open government movements promises public disclosure that enhances civic accountability. Together, the movements seek information that enhances service delivery andpublic integrity, both because the information is important and politically relevant and because it is released in formats that ensure its widespread use and reuse. It is thus the upper-right-hand quadrant of Yu and Robinson’s diagram that needs the most attention and that can most benefit from the collective power of these two movements.

Indeed, the collaboration between open data and open government may be beneficial for both movements. Open data benefits open government by focusing attention on the users’ needs, thereby increasing public disclosure’s potential value to citizens and harnessing technology to make the most of available information. But open data also benefits from open government, which links public disclosure to core governance problems and promises that the technical community behind open data might meaningfully deploy its expertise and energy to strengthen accountability in democracies around the world.

These are hypotheses about how a big tent might be helpful, both to citizens seeking greater openness in their own countries and to advocates of open data and open government internationally. It is too early to know whether Yu and Robinson’s pessimistic take captures where we are headed, or whether the possibility of harnessing this collaboration to drive greater openness across many domains can be realized. Our experiences, however, lead us to believe that the more optimistic outcome is a real possibility.

III. The Kenya Example

In new and emerging democracies, there is no more politically relevant issue than the quality of public services. While activists and voters in developing countries, like those in developed countries, also focus on classic governmental transparency issues, such as freedom of information and access to public meetings, they are primarily concerned with failures of service delivery. Indeed, transparent government performance is critical to the effective functioning of democratic institutions, as information on service delivery allows politicians to provide oversight on the performance of public bureaucracies while enabling citizens to monitor the service providers and provide feedback to the politicians via the electoral process.[ref]See Rohini Pande, Can Informed Voters Enforce Better Governance? Experiments in Low-Income Democracies, 3 Ann. Rev. Econ. 215 (2011).[/ref]

In fact, in the arena of service delivery, open data has paved the way for government accountability even when traditional reforms have stalled. The Kenya Open Data Initiative, launched by President Mwai Kibaki in July 2011, is driven both by an interest in innovation and government modernization and by an interest in “determining whether Government is delivering services effectively and accountably.”[ref]Mwai Kibaki, President & Commander-in-Chief of the Def. Forces of the Republic of Kenya, Speech at the Launch of the Kenya Government Open Data Web Portal at the Kenyatta International Conference Centre, Nairobi (July 8, 2011), available at http://www.statehousekenya.go.ke/speeches/kibaki/july2011/2011080702.htm.[/ref] By January 2012, the Kenya Open Data Portal had released over four hundred data sets, ranging from geomapped school facilities and national census information to fiscal data and Community Development Fund spending.

To be sure, some of the most sensitive data sets remain shrouded in secrecy. However, open data is harnessing the ingenuity and creativity of a new generation of technologists who are applying their unique expertise to maximize the impact of public data and cultivate the demand for further openness. For example, EduWeb,[ref]EduWeb, http://www.eduweb.co.ke (last visited Oct. 20, 2012).[/ref] launched by a Kenyan entrepreneur, is an interactive site that pulls from open data to help parents compare local school performance. The site is a tool for citizens to make informed choices about their children’s education and is also beginning to affect policies in the Ministry of Education, which is considering significant changes to its approach to sharing data with the public. Moreover, while Kenya has the benefit of an emerging network of intermediaries and technologists who can harness newly available data, citizen groups are also rising to the challenge. Local citizen empowerment organizations, such as Uwezo and Twaweza in East Africa, are prioritizing access to data on performance and finding creative ways to make it available and understandable for citizens in an effort to spur political and social action.[ref]See, for example, Twaweza, Annual Report 2011 (2012), available at http://twaweza.org/uploads/files/Twaweza%20Annual%20Report%202011.pdf, for an overview of Twaweza’s approach to achieving social accountability by making local service delivery performance information widely available.[/ref]

Open data is also playing a role in transforming one of the primary drivers of accountability in emerging democracies: the media. Code for Kenya, an initiative launched by a consortium of public sector, media industry, and technology partners in July 2012, placed an initial class of four technology fellows in the largest media houses in Kenya to scale dramatically the use of open data across the country.[ref]Code 4 Kenya, http://code4kenya.org (last visited Oct. 20, 2012).[/ref] Fellows are currently developing tools ranging from an election portal to compare candidate rhetoric against local performance metrics to a mobile tool to provide information about ailments and appropriate local health care. Code for Kenya thus promises both transparency and innovation in government operations. Citizens can get better information about local services while media companies are transforming themselves into data companies. Several government ministries have already expressed interest in hosting the next class of fellows.

Finally, Kenya’s open data movement, while initially centered on a single platform, has sparked a new way of doing business across some government line ministries. In August 2012, the Ministry of Lands launched a platform allowing the public to view the location, acreage, current use, and geocoordinates of public lands. As one member of parliament noted, “A lot of land was grabbed in the past and we know corrupt individuals are still waiting for a chance to encroach the remaining parcels. . . . But if the people know what asset belongs to them then Constituency Development Funds (CDF) would not be used for these purchases.”[ref]David Njagi, Digital Mapping of Public Land to Curb Graft in Kenyan Counties, Bus. Daily Afr., (Aug. 12, 2012, 4:24 PM), http://www.businessdailyafrica.com/Corporate+News/Digital+mapping+of+public+land+to+curb+graft+in+Kenya+counties++/-/539550/1477520/-/8h6gepz/-/index.html (internal quotation marks omitted) (recounting remarks of Bernard Kinyua, District Commissioner of Lari).[/ref] The Ministry of Lands is not alone. In September 2012, Kenya’s public hospital system built and deployed a low-cost, open-source e-health system, saving over $1.9 million compared to proprietary solutions, while improving service delivery and publishing performance records.[ref]See Steve Mbogo, Kenya Rolls Out Open-Source e-Health System, E. Afr. (Sept. 15, 2012, 12:58 PM), http://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/business/Kenya+rolls+out+open+source+ehealth+system/-/2560/1508146/-/14p76lfz/-/index.html.[/ref] Finally, Kenya’s largest education data holders, the Ministry of Education, the National Examinations Council, and the Teacher Service Commission, are launching a National Integrated Education Information Management System, inspired by open data best practices and developed with feedback from Code for Kenya fellows. While Parliament waits to debate Kenya’s Freedom of Information Bill, an effort to codify transparency in law, early adopters across the bureaucracy are already taking steps to leverage open data in ways that matter to citizens.

IV. The International Example

Kenya is just one example realizing the promise of open data and open government together. On the broader international stage, the possibility of a productive partnership between these two movements is also coming into fuller view. The Open Government Partnership—which now counts fifty-seven countries among its members—launched with a big tent view of openness in mind. The Open Government Declaration[ref]The Open Government Declaration, Open Gov’t P’ship (Sept. 2011), http://www.opengovpartnership.org/open-government-declaration.[/ref] commits countries to achieve high-level, aspirational goals around transparency, responsiveness, accountability, and effectiveness. Although it is too early to judge the full impact of this nascent effort, some early data suggests that worries that concrete actions would not match these commitments may be unfounded.

Forty-five governments submitted comprehensive action plans as required by the Partnership detailing the concrete steps they will take to put their commitments into action.[ref]See Abhinav Bahl, So What’s in Those OGP Action Plans, Anyway?, Global Integrity (July 26, 2012, 10:11 AM), http://globalintegrity.org/blog/whats-in-OGP-action-plans.[/ref] Global Integrity’s early assessment of the plans provides reason to be optimistic about the potential for open data to enable open government. While open data and new technologies figure prominently among the pledges—accounting for nearly one-third of the commitments—governments have also made robust commitments to enhance citizen engagement and improve access to information through more traditional initiatives, such as legislation and government training programs.[ref]See Nicole Anand, Assessing OGP Action Plans, Global Integrity (June 21, 2012, 12:10 PM), http://globalintegrity.org/blog/ogp-action-plan-assessments.[/ref]

Moreover, there is evidence that the commitments are not simply aspirational ones. Global Integrity evaluated the plans in terms of five criteria: Were plans specific, measurable, actionable, relevant, and time bound? This is a high bar to set for political commitments on an international stage in any process, and the results are encouraging. More than 70 percent of submitted plans meet at least four of the five criteria.[ref]Id.[/ref]

Instead of open data and technology crowding out traditional open government activities, the comprehensive nature of these action plans suggests that the merging of the movements is spurring progress across a wide variety of areas under the big tent. Why are Yu and Robinson’s fears not coming to fruition? At least in the Open Government Partnership, the answer lies in the design of the initiative itself: minimum country membership conditions that focus on traditional metrics of openness and accountability, a declaration and guidance for action plans that emphasizes comprehensiveness and recognizes the coexistence of distinct agendas, and a chorus of civil society activists providing input and oversight of the process, each with their own issue areas and interests. These conditions thus decrease the likelihood that governments can easily substitute show for substance as Yu and Robinson fear.

Conclusion

Conceptual clarity about the distinct meanings of open data and open government will benefit everyone. But the power of a close partnership between these two movements is also becoming evident. The big tent is strengthening both movements and creating opportunities for progress in places where traditional reforms have stalled or failed to fulfill their promises. While clarity about distinct goals and policies is welcome, separation risks setting back an emerging, more unified movement that is bringing technology and innovation to the age-old task of making government work for people.