Introduction

As much attention has been focused on scrutinizing President Trump’s two appointments to the United States Supreme Court, a more pervasive and insidious effort by President Trump to remake the federal judiciary has gone relatively unchallenged.1 Our collective obsession with the nation’s highest court and its shifting ideological balance since the retirement of longtime moderate Justice Anthony Kennedy, while important, has allowed a less notable but no less important shift to occur in the judiciary as a result of Trump’s record-setting pace of appointments to the lower federal courts.2 Aside from their obvious politics, most of Trump’s judicial appointees share something else in common—they are almost all white and largely male.3 This is no mere coincidence. It is a seemingly deliberate attempt to undo decades of diversity progress on the federal judiciary made over the course of multiple, successive presidential administrations across both political parties.4

For all the handwringing over President Trump’s two appointees to the Supreme Court, the president has quietly appointed more judges to the federal appeals courts in his first two years in office than any other president in history.5 Given that so few cases will ever be heard by the Supreme Court, these courts often represent the highest level of appeal in our federal judicial system.6 In addition to being prolific, there is a striking pattern to Trump’s judicial appointees. He has broken with a decades-long presidential tradition of making the judiciary more demographically diverse than one’s political predecessor.7 Instead, Trump has appointed fewer minority judges to the federal bench than any president since Ronald Reagan and fewer women judges than any president since George H.W. Bush.8 For the first time in nearly three decades, the federal bench has actually become appreciably less diverse, even as the nation has continued to experience rapid growth in its demographic diversity.9 The truculence about America’s growing cultural pluralism that is reflected in Trump’s federal judicial appointments is resonant with a central theme of his now (in)famous campaign promise. Notwithstanding the facile appeal to patriotism, there is considerable proof that what Trump really aims to do is not “Make America Great Again” so much as “Make America White Again.”10 At least insofar as his efforts to remake the judiciary are concerned, this “whitewashing” has grave consequences for the judiciary itself and arguably for our democracy more broadly.11

Trump’s record-setting pace of federal judicial appointments have shifted the demography of the judiciary from one that was becoming increasingly more representative of the people it serves to one that is actively being made less representative of the American people. This Article first highlights this demographic shift in quantifiable terms. It then situates this judicial trend as a part of Trump’s larger political agenda and explores its consequences for the judiciary and for our ideals of democracy more broadly.

I. The History of Diversity in Federal Judicial Appointments

Article II of the U.S. Constitution grants the president power to appoint federal judges subject to the advice and consent of the U.S. Senate.12 This gives the president enormous power to influence the composition of the federal judiciary. In an attempt to balance the executive’s influence over the judicial branch, Article III grants lifetime tenure to federal judges.13 Lifetime tenure promotes judicial independence, but it also slows the process of judicial turnover.14 This explains why the judiciary remains predominantly white and male notwithstanding sustained efforts to diversify the federal bench across successive presidential administrations since 1977.15 It also explains why Trump’s efforts to reverse this modern trend towards greater judicial diversity are so troubling. The consequences of Trump’s actions will endure long past the end of his presidency. Prior presidential efforts to increase the diversity of the judiciary that have spanned nearly the last half century will be eroded for decades to come. This is occurring precisely as the country is rapidly shifting towards greater cultural pluralism, and as political attitudes have begun to embrace representative diversity as necessary to the pursuit of democratic equality.16

It will come as no surprise that beginning with the first presidential appointment to the Supreme Court in 1789 and continuing through 1933, every judge appointed to the federal bench was a white man.17 It was not until 1934 that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt appointed the first woman to a federal court of general jurisdiction.18 Roosevelt also appointed the first person of color to the federal bench when he nominated William H. Hastie to serve on the federal district court for the U.S. Virgin Islands in 1937.19 Prior to the Civil Rights Movement, presidents seldom appointed a minority or woman to serve on the federal judiciary, keeping the number of women and minority judges on the bench exceedingly low. From 1934 until 1960, of the 1337 judges appointed to the federal bench, only two were white women and another two were men of color.20 However, beginning with President John F. Kennedy, the rate of women and minority judges appointed to the federal bench rose appreciably.21 Although he served less than three years in office, Kennedy appointed five minority men and one white woman to the federal bench.22 When Lyndon B. Johnson assumed the presidency, during the apex of the Civil Rights Movement, he surpassed Kennedy’s record by appointing twelve minority judges and three women judges, including one woman of color, to the federal bench.23 It was President Johnson who appointed the first minority Justice to the Supreme Court when he nominated, and the senate confirmed, Justice Thurgood Marshall in 1969. The Civil Rights Era seemed to mark the point of acknowledgment, albeit tacit, that the judiciary must, even nominally, reflect the diversity of citizens in order to be viewed as legitimate in our representative democracy.

It was not until 1977, when President Jimmy Carter announced his commitment to diversifying the federal bench, that this acknowledgment was made explicit, and the appointment of women and minority judges to the bench increased dramatically.24 President Carter appointed forty women judges (eight of them minorities) and fifty-seven minority judges (eight of them women) to the federal bench during his single four-year term.25 This was more than twice the number of women and minority judges appointed during the previous four administrations combined.26 Although Ronald Reagan did not express a commitment to judicial diversity during his two terms as president, even he broke a historic barrier in 1981 by appointing Sandra Day O’Connor as the first female Justice of the Supreme Court.27

Reagan’s successor, George H.W. Bush (Bush I) improved on his predecessor’s diversity performance significantly, increasing the share of women judges he appointed by 138 percent over Reagan and increasing the share of minority judges he appointed by 59 percent.28 Then in 1994, President Bill Clinton renewed Carter’s express mandate of diversifying the federal bench by proclaiming his commitment to make his appointments “look like America.”29 Clinton’s federal judicial legacy includes appointing 104 women judges (including twenty-one minorities) and ninety minority judges (including twenty-one women) to the bench.30 Perhaps most notably, President Clinton added a second female Justice to the Supreme Court with his appointment of Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1993.31

President George W. Bush (Bush II), did not increase the diversity of the federal judiciary at the same rate as Clinton, but his appointments were more diverse than both of his Republican predecessors.32 In fact, continuing the Carter and Clinton legacy of making explicit what often had been only tacitly acknowledged, Bush II reportedly insisted that his judicial nominees reflect adequate racial and gender diversity.33 This commitment resulted in a 75 percent increase in the share of minority judges appointed by Bush II relative to Bush I.34 Bush II’s express desire to nominate women and minority judges to the federal bench, and his success in doing so, affirmed the importance of judicial diversity even among modern Republican presidents.35

By far the most notable increase in the diversity of the federal judiciary came during the first black presidency.36 Although not known for making any express commitment to improving judicial diversity, President Barack Obama’s actions spoke louder than any words could.37 Obama appointed more women and minority judges to the federal bench than Reagan and both Bushes combined.38 He appointed 137 women judges and 118 minority judges to the bench, including more Asian American women than all forty-three of his presidential predecessors combined.39 While Reagan and Clinton each appointed a single female Justice to the Supreme Court, Obama was the first president to appoint two women to the Supreme Court, one of whom was also the first Hispanic Justice appointed to the nation’s highest Court.40 These appointments tripled the number of women on the Supreme Court (from one to three), making the Court more closely resemble the gender demography of the country than ever before.41

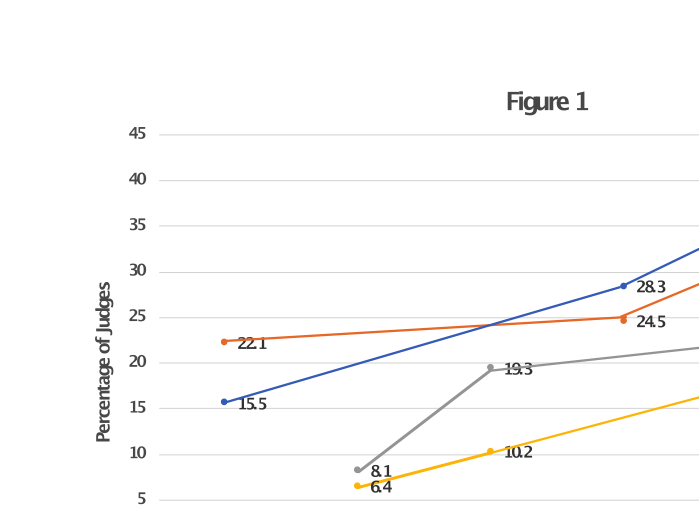

Analysis of data compiled by Jonathan Stubbs regarding the demographics of federal judicial appointments from Carter through Obama show a trend of increasing diversity among judicial appointees across both Democratic and Republican administrations.42 That is to say while Republican presidents have appointed fewer minorities and women to the federal bench than their Democratic counterparts, the diversity of judicial appointments trends upwards among Republican as well as Democratic presidents over time.43 (See depicting this trend analysis).

More specifically, this analysis of Stubbs’s data show that among Democratic presidents, Carter appointed only 15.5 percent women judges and 22.1 percent minority judges to the bench, but Clinton appointed 28.3 percent women judges and 24.5 percent minority judges. Then Obama appointed more women (42.3 percent) and minority (36.4 percent) judges to the bench than both Carter and Clinton. The data similarly show that among Republican presidents, Reagan appointed only 8.1 percent women judges and 6.4 percent minority judges to the bench. While Bush I appointed 19.3 percent women judges and 10.2 percent minority judges, and Bush II appointed more women (22.1 percent) and minority (17.8 percent) judges to the bench than either of his Republican predecessors.44 This increasing trend of diversity in judicial appointments across both political parties reflects at least a tacit, and at times explicit, presidential acknowledgement of the importance of diversity to the federal bench.45 By contrast, President Trump’s appointments to the federal bench in his first two years mark a conspicuous, and seemingly deliberate, shift in this trend. His appointments suggest not only a rejection of the value for judicial diversity displayed by his presidential predecessors, but also an attempt to undermine the diversity progress achieved on the federal bench over the last several decades and across both political parties.

II. Trump’s Judicial Appointments by the Numbers

Due to delays in senate confirmation of many of President Obama’s judicial nominees under majority leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), President Trump inherited an unusually large number of vacancies on the federal court.46 In total, Trump has already had the opportunity to fill approximately 216 of the 890 seats on the federal court, “or almost 25 percent of the entire federal bench” in just his first two years in office.47 Trump and McConnell took advantage of this opportunity by prioritizing, among other things, the nomination and confirmation of federal judges.48 As a result, Trump has appointed more federal appellate judges in his first two years in office than any other president in history.49

As a Republican president, it is not at all unexpected that Trump has used the nominations process to appoint conservative judges to the bench.50 What is worrisome, especially given the recent trend even among Republican presidents towards increasing diversity on the federal bench, is that Trump’s judicial appointees have been woefully lacking in diversity.51 Although snapshots of the demographic profile of the federal judges appointed by Trump vary slightly depending on the timing, an independent analysis of Trump’s judicial appointees from demographic data compiled by the Federal Judicial Center suggests that of the eighty-three judges confirmed in Trump’s first two years in office, only seven are minorities and twenty are women (including two women of color), making his appointees 92 percent white and 76 percent male.52 This represents a dramatic slide backwards from the very diverse appointments made to the bench by Trump’s immediate predecessor Obama, whose appointments were only 64 percent white and 58 percent male.53 But it also represents a notable regression from the diversity of appointments made to the federal bench by Bush II, Trump’s most recent Republican predecessor. Bush II’s record on judicial diversity belies any claim that the lack of diversity among Trump’s judicial appointees is merely an inadvertent consequence of his ideological commitment to appoint conservative judges, rather than a deliberate aversion to diversifying the federal bench.54

Trump has appointed white men in numbers not seen in nearly three decades, reversing a four-decade trend across both Democratic and Republican administrations of increasing the diversity of judges appointed to the federal bench over time. Among Democratic presidents, the share of white males appointed to the bench shrank from 66 percent during Carter’s Administration, to 53 percent during Clinton’s administration, and they represented a mere 36 percent of Obama’s appointees to the bench.55 Republican presidents have appointed more white males and fewer diverse judges to the bench compared to Democratic presidents. Until now, however, they too evidenced a trend towards greater judicial diversity with the share of white male judges appointed by Reagan at 86 percent, but falling to 73 percent under Bush I and falling yet again under Bush II to 67 percent.56 Trump has reversed this decade-long trend by appointing approximately 70 percent white male judges to the federal bench.57

This pattern is difficult to explain as anything other than Trump’s deliberate attempt to reverse the decades-long trend by his presidential predecessors (across both Democratic and Republican administrations) of increasing the diversity of the federal bench.58 None of the nearly fifty federal appellate judges nominated by Trump in his first two years in office were African American, despite representing the largest share of sitting minority judges, and none were Hispanic, the second largest minority group among sitting federal judges.59 In addition to failing to nominate women and minority judges who would increase the diversity of the bench, in multiple instances Trump has further reduced the diversity of the federal bench by replacing women and minority judges with white men.60 Rorie Solberg and Eric Waltenburg, who study and have written extensively on the diversity of the federal judiciary, measured the extent to which judicial appointments have increased, decreased, or maintained the diversity of the federal bench across successive presidential administrations.61 They report that Trump has nominated the lowest share of judges who have increased the diversity of the bench since Ronald Reagan.62 More tellingly, Trump has nominated the highest share of judges who have decreased the diversity of the bench (by a margin of more than two to one) since before the Carter Administration.63

Although efforts to increase diversity are often erroneously criticized for sacrificing merit in service to diversity, even this cannot explain the lack of diversity among Trump’s judicial appointees.64 In fact, Trump has turned this standard critique on its head.65 In his first two years in office, Trump has not only nominated a higher share of white male judges than any recent president, he has also nominated more judges deemed “not qualified” by the American Bar Association than any other president in the first two years of office.66 Beyond concerns over their lack of diversity, Trump’s nominees raise even greater questions of judicial legitimacy and competence.67

Trump’s ostensible effort to undermine or actively reverse the decades of diversity progress made on the federal bench is notable for its startling contrast with modern presidential practice, but it is also concerning because of its dangerous implications for the legitimacy and effective functioning of our judiciary in an increasingly diverse nation.68 Because federal judges are appointed for life, Trump’s judicial legacy is likely to be felt for generations to come and will be difficult to reverse over the next several successive presidential administrations.69 In other words, the diversity hole that Trump is digging on the federal bench will not likely be filled in the near term. The legacy Trump is leaving behind is a federal judiciary that is becoming more white and more male at precisely the moment when our nation is becoming more diverse, our democracy is increasingly reflective of that diversity, and a majority of citizens are demanding even greater democratic accountability to those diverse constituencies.70

III. “Make America Great Again” or “Make America White Again”?

It is important to recognize that Trump’s actions do not appear inadvertent; nor are they simply an inconsiderable byproduct of his commitment to appoint conservative judges.71 Trump’s appointment of predominantly white male judges to the federal bench seems to be the realization of a promise made during his campaign to “Make America Great Again” and reveals, with startling clarity, the true message behind this often-repeated political mantra. If there was any doubt, one need only look at Trump’s actions since taking office to gain insight into its thinly veiled meaning.72 From the executive order imposing a ban on Muslims entering the country that Trump signed almost immediately after taking office,73 to his administration’s relentless assault on “Mexican immigration,” including his willingness to shut down the federal government over funding for the southern border wall,74 Trump’s open hostility towards the presence of certain minority groups in this country has been palpable. His determined insistence to reverse a decades-long trend often identified as the “browning of America” is equally evident in his administration’s stepped-up efforts to revoke citizenship for already naturalized persons,75 as well as his publicly professed desire to limit future immigration from African countries, while simultaneously increasing immigration from predominantly white countries.76 Trump has provided ongoing, unassailable proof of his political ambitions to curb the current trend towards greater demographic diversity in our nation (much of which has been fueled by immigration).77 These are not nominal policy concerns reflected in trivial administrative decisions. They have been championed by the president himself and have been accomplished through the direct exercise of the president’s own executive power.78

Trump’s antipathy to increasing American multiculturalism is further evidenced by his association with and public demonstrations of support for those who espouse racist and white supremacist rhetoric.79 His appointment of people to prominent positions within his administration who have noted ties to white nationalist and alt-right organizations, or who have expressed white nationalist ideologies themselves, exposes Trump’s true political agenda.80 So too does his willingness to countenance the violence and intimidation committed by white supremacists, as exhibited most recently following the Unite the Right march in Charlottesville, Virginia when Trump failed to unequivocally condemn these alt-right protesters, one of whom killed a counter protester, and instead described them as “very fine people.”81 Observations about the “race-baiting” nature of Trump’s “Make America Great Again” mantra, or his racially-motivated actions as president, are far from new and are hardly isolated.82 They are common and have been widely acknowledged.83 This strategy of white-racial appeal masquerading as conservative populism, also known as “dog-whistle politics,” has a long history among Republican presidents, dating back to southern backlash against the passage of the Civil Rights Act.84

Trump’s judicial appointments appear to be part and parcel of his professed political ambition to “Make America Great Again,” which bespeaks an effort to instead “Make America White Again.” Although cloaked in Republican rhetoric, the reason for his appointment of largely white and mostly male judges is more insidious than a desire for “originalist [judges] in the mold of the late Justice Antonin Scalia.”85 Any such claim is belied by the demographic pattern of judicial appointments made by Trump’s Republican predecessors who have appointed conservative, originalist judges while still increasing judicial diversity.86 The most notable example is Justice Clarence Thomas, the sole black sitting Justice of the Supreme Court, who was nominated by Bush I and ranks as more conservative than all other modern Supreme Court Justices, including the late Justice Antonin Scalia himself.87 History proves that conservatism can be reconciled with judicial diversity. Instead of prioritizing a commitment to conservatism, President Trump seems determined to reverse the course of history, roll back decades of diversity progress made by his presidential predecessors, and whitewash the federal judiciary, even though majorities of Americans believe our government is already too white and far too male.88

His efforts not only abandon decades’ worth of work to diversify the federal judiciary across successive presidential administrations of both political parties, they also run counter to current demographic trends demonstrating that the country is rapidly diversifying and public opinion polls showing that Americans increasingly expect the government to reflect that diversity.89 Scholars were already raising alarms before Trump’s election about the grave threats to the legitimacy and effective functioning of the judiciary occasioned by the failure of the judiciary to keep pace with the rapidly increasing diversity of the nation.90 Trump’s efforts to widen this gulf even further, and for generations to come, only serves to heighten these concerns.

IV.The Imperative of Judicial Diversity

Before Trump took office the federal judiciary was comprised of roughly 60 percent white males, 20 percent white women, and 20 percent racial and ethnic minorities.91 This diversity profile still falls far short of reflecting the demographics of the population, which is comprised of only about 30 percent white men, 30 percent white women, and 40 percent racial and ethnic minorities.92 But, as already noted, this progress was hard won and achieved incrementally over the course of six successive presidential administrations across both political parties.93 Against this trend, and in the face of increasing diversity among the general population, Trump has appointed 70 percent white men, 21 percent white women, and a paltry 8 percent racial and ethnic minorities to the federal bench.94 Current census projections predict the overall population will become majority minority sometime around 2042 when many of these overwhelmingly white and mostly male Trump appointees will still be sitting on the federal bench.95 Recent data released by the Pew Research Center suggests that the generation defined as post–millennials, or Generation Z, will reach this critical majority minority threshold by 2026, when they will be between the ages of fourteen and twenty-nine.96 The predominantly white and largely male judiciary Trump is installing now will be even more out of step with the population it will be called upon to serve in the near future.

More important for the consequences of Trump’s largely white male judicial legacy than its failure to reflect the growing diversity of the population is that it also cannot be reconciled with shifting political attitudes, especially among younger generations of Americans who, unlike Trump himself and others of his baby boomer generation, view increasing diversity as a social good to be encouraged, rather than a social ill to be cured.97 The same Pew study found that even among Republicans this difference is stark. More than half of all post–millennial Republicans agreed that increasing racial and ethnic diversity is good for the country, compared with a third of baby boomer Republicans.98 This means that future generations of Americans will inherit a judiciary that fails to adequately reflect their value for diversity.

It is not just the millennial and post–millennial generations who reject Trump’s vision of America. The Reflective Democracy Campaign, a research and advocacy organization committed to analyzing demographic trends in politics, conducted a survey of 800 registered voters and solicited their thoughts on the current demographic trends in government.99 Both Democratic and Republican respondents shared the belief that there are too many white men and too few women and minorities in elected offices.100 Perhaps more surprising, over three-quarters (77 percent) of respondents said they support affirmative efforts to increase the number of women in office and nearly three-quarters (71 percent) said the same about increasing the number of minorities in office.101 So any belief on Trump’s part that this “whitewashing” of the judiciary will be viewed positively, or that voters will see it as an improvement over the status quo (i.e. that these efforts will “Make America Great Again”) is contradicted by this data.

Indeed, consistent with this growing support for American democratic pluralism, the country has been blazing all sorts of new diversity trails. Americans elected the first nonwhite president in 2008, and that president appointed the first Hispanic and woman of color to the Supreme Court in 2009.102 Obama was also the first president to appoint two women to the Supreme Court, bringing the total number of sitting female Justices to an all-time high of three.103 Democrats nominated the first woman to run for president on a major party ticket in 2016, and despite her loss in the general election, Americans sent more women and people of color to the U.S. Congress during the 2018 midterm elections than at any time in our nation’s history.104 Notable firsts on behalf of women and minorities in all branches of the federal and state government have occurred continuously over the last several decades.105 Trump’s overwhelmingly white and largely male judicial appointments imperil the diversity progress our nation has achieved and threaten to erode the increased sense of democratic legitimacy associated with that progress.

In addition to presidents of both political parties, beginning with the Carter Administration in 1977 and running all the way through the Obama Administration in 2016,106 legal scholars and political scientists alike have long recognized the link between judicial diversity and the appearance of judicial legitimacy.107 Citizens of all races and ethnicities are more likely to believe that our justice system is fair and equitable to all when judicial decisionmakers reflect the diversity of the citizenry.108 Conversely, citizens often question the fairness and legitimacy of the judicial process when judicial decisionmakers fail to reflect the diversity of those who appear before the court.109 The most prominent historic examples of this occurred when all-white juries convicted black defendants (often wrongly) whose victim was white.110 More recently, there has been public outcry over all-white juries acquitting white defendants (often police officers) whose victim is black.111 These events have been all too common in our nation’s history and have sparked outrage (and occasionally protest) from those who assert that even the semblance of injustice in these cases, arising from the gross racial disparity between those who sit in judgment and those being judged, impugns the court’s legitimacy.112 This undermines citizens’ trust in the justice system, as well as their faith in the rule of law.113

The federal judiciary relies heavily on the appearance of legitimacy to engender citizens’ trust and secure their willingness to submit to the authority of the court and adhere to the rule of law.114 According to the theory of procedural justice, it is the appearance of fairness in the judicial process, even more than the outcomes themselves, that fosters the trust among citizens necessary to legitimize the judicial process.115 In a 2002 study of 1,656 respondents who interacted with the justice system, respondents’ perceptions of the fairness of the process were more determinative of respondents’ willingness to accept the decision of the court than was the favorability of the decision itself.116 In other words, even when judicial decisions are unfavorable, citizens are more likely to accept and adhere to the law when they believe the decisions result from a fair process. When judicial decisionmakers are diverse, it enhances these perceptions of fairness in the judicial process.117 There is a growing consensus that all branches of government must reflect the diversity of citizens in order to be viewed as legitimate.118 This recognition of the link between the diversity of public officials and our ideals for democratic equality has deep historic roots in America.119 Although we have long struggled to realize this ideal for greater diversity among our civic leaders, progress has been made, including among federal judges.

For the first 145 years of our nation’s history, the federal judiciary was comprised of all white men.120 Prior to the 1960’s, only a handful of women and minority judges were appointed to the federal bench, but this began to change during the Civil Rights Era.121 Then in 1977 President Carter announced a commitment to diversifying the federal judiciary, and meaningful progress to increase diversity on the federal bench began.122 Since that time, every president has built upon the diversity progress of their political predecessor to gradually improve the diversity of the bench over time.123 As a result of these sustained efforts, a judiciary that just fifty years ago was comprised of more than 93 percent white men, is now comprised of 20 percent racial and ethnic minority judges and more than a quarter women judges.124 Not only does this increased diversity improve citizens’ perceptions of judicial legitimacy, there is also evidence that it increases judicial functioning by making judges more accountable to minority interests.125

The theory of representative bureaucracy posits that racial congruence between bureaucrats, such as judges, and the citizens they serve improves bureaucratic decisionmaking on behalf of minority interests, particularly on issues of high racial salience.126 The deliberative and epistemic benefits of diversity for judicial decisionmaking can be seen in trial court rulings in discrimination cases,127 appellate court rulings in civil rights cases,128 and even in contested Supreme Court cases.129 These diversity benefits are not simply a function of more progressive ideological commitments among minority judges. In one study of judges’ decisions in discrimination cases, minority judges ruled in favor of minority plaintiffs more often than their white counterparts by a sizeable margin, regardless of party of appointment.130

V. The Danger of Trump’s Judicial Legacy

Procedural justice suggests that perceptions of fair process are important for generating the trust necessary to legitimize the judiciary in the eyes of citizens,131 but this trust will eventually erode if minority groups suffer continual losses in the justice system.132 Minority citizens must believe in the legitimacy of the judicial process, but ultimately, they must also believe that their interests will be effectively and fairly served by that process. Diversity among judges provides both the legitimacy and accountability necessary for all citizens to trust in the judicial process and submit to the rule of law. It should, therefore, be troubling that the progress made since 1977 in diversifying the federal judiciary is now being eroded by President Trump.

Trump’s reversal of this modern trend towards increasing judicial diversity not only breaks with past presidential tradition, it also threatens the legitimacy and effective functioning of the judiciary in an increasingly diverse America. In a nation that is comprised of thirty percent white men, thirty percent white women, and forty percent racial and ethnic minorities, Trump’s judicial appointees have been ninety-two percent white and seventy-six percent male.133 This “whitewashing” of the federal judiciary under President Trump may cause citizens to question the legitimacy of the judicial processes presided over by these judges who are once again overwhelmingly white and mostly male. This will compromise public trust in the judiciary and reduce judicial accountability to an increasingly diverse citizenry.

Trump has rebuffed the effort to improve judicial diversity reflected across successive presidential administrations, despite persistent pleas among scholars and growing calls among citizens to sustain and even improve upon these efforts.134 More troubling still, the judicial appointments made during Trump’s first two years in office reveal a president who is actively seeking to make the federal judiciary less diverse.135This“whitewashing”ofthejudiciaryiscontrarytomodernpresidentialtrends,prevailingpublicwisdom,andperhapsmostimportanttheturningdemographictideinAmerica.

Conclusion

Demographers predict a nation that will become majority minority within the next generation. Opinion polls reflect that citizens across the political spectrum increasingly want our nation’s leaders to reflect the growing diversity of the population, and believe further that improving the diversity of our leaders is good for democracy. Data and research bear out these beliefs by showing that increased judicial diversity improves not only perceptions of judicial legitimacy but the effective functioning of our judiciary. In light of all this, Trump’s seemingly deliberate attempts to undermine judicial diversity are both inexplicable and indefensible. They diminish rather than enhance our democracy. And they move us further from, rather than closer to, our ideals of equality and justice. The question we must ask is whether these efforts are truly an attempt to “Make America Great Again,” or just a way to “Make America White Again?” If it is the latter, Americans have spoken, and the evidence is clear, Trump’s judicial legacy poses a dangerous threat to judicial legitimacy and ultimately to our ideals for American democracy.

[1]. In January 2017 Trump nominated, and the U.S. Senate confirmed, Justice Neil Gorsuch to replace Justice Antonin Scalia, who died in February 2016. In July 2018, Trump nominated Justice Brett Kavanaugh to replace retiring Justice Anthony Kennedy, but Kavanaugh was not confirmed by the senate until October 2018 due to controversy over his judicial record, prior writings, and allegations of sexual misconduct. See Sophie Tatum, Brett Kavanaugh’s Nomination: A Timeline, CNN (Oct. 2018), https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2018/10/politics/timeline-kavanaugh.

[2]. See infra text accompanying note 47.

[3]. See infra text accompanying note 52.

[4]. See infra text accompanying note 58.

[5]. See infra text accompanying note 49.

[6]. See Barry J. McMillion, Cong. Research Serv., R45189, U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominations During President Trump’s First Year in Office: Comparative Analysis With Recent Presidents 1 (2018).

[7]. See infra text accompanying notes 55–57.

[8]. See infra text accompanying notes 44, 52.

[9]. See infra text accompanying note 89.

[10]. See infra Part III.

[11]. See infra Parts IV–V.

[12]. U.S. Const. art. II, § 2.

[13]. U.S. Const. art. III, § 1; see also McMillion, supra note 6, at 1.

[14]. See Steven G. Calabresi & James Lindgren, Term Limits for the Supreme Court: Life Tenure Reconsidered, 29 Harv. J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 769, 771 (2006).

[15]. Though snapshots of the demographic profile differ, one examination of sitting judges shows the judiciary was 74.2 percent male (25.8 percent female) and 79.7 percent white (20.3 percent minority) as of March 10, 2016—just months before Trump assumed office. See Jonathan K. Stubbs, A Demographic History of Federal Judicial Appointments by Sex and Race: 1789–2016, 26 Berkeley La Raza L.J. 92, 117 (2016). Another snapshot of “active judges” as of June 1, 2017—after the end of President Obama’s second term but before many of President Trump’s judicial nominees were confirmed—shows the judicial profile as 65.3 percent male (34.7 percent female) and 72.1 percent white (27.9 percent minority). See Barry J. McMillion, Cong. Research Serv., R43426, U.S. Circuit and District Court Judges: Profile of Select Characteristics 4–5, 15, 17 (2017). These latter figures were calculated by combining the number of women judges on both the district and circuit courts, as well as the number of minority judges on both the district and circuit courts, as of June 1, 2017, then dividing each by the total number of sitting judges on both the district and circuit courts as of that date. Id.

[16]. See infra text accompanying notes 97–101.

[17]. Stubbs, supra note 15, at 99.

[18]. Roosevelt nominated Florence Ellinwood Allen, a white woman, to the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit on March 6, 1934 and she was confirmed by the senate on March 15, 1934. Id. at 101. Calvin Coolidge previously appointed Genevieve Rose Cline, also a white woman, to the U.S. Customs Court. Id.

[19]. Id. Although Hastie, a black man, served in the U.S. Virgin Islands for only two years, President Truman gave him a recess appointment in 1949 to serve on the Third Circuit Court of Appeals. Id. at 101–02.

[20]. Id. at 109.

[21]. Id. at 103.

[22]. Id.

[23]. Id. at 111. Johnson appointed the first woman of color to the federal bench when he nominated Constance Baker Motley to serve on the federal district court in New York. Id. at 103–04.

[24]. Nancy Scherer, Diversifying the Federal Bench: Is Universal Legitimacy for the U.S. Justice System Possible?, 105 Nw. U. L. Rev. 587, 594 (2011).

[25]. Stubbs, supra note 15, at 111. By contrast, Nixon, Carter’s immediate predecessor, appointed nine men of color and one white woman to the bench. Id. at 104, 111. Ford, who assumed the presidency when Nixon resigned, appointed only a quarter of the number of judges appointed by Nixon and they included six men of color and one white woman. Id. at 111.

[26]. Id.

[27]. Id. at 107.

[28]. Id. Bush I appointed nineteen minority judges (including five women) and thirty-six women judges (including five minorities) to the federal bench during his single term. Id. at 107, 111.

[29]. Scherer, supra note 24, at 601.

[30]. Stubbs, supra note 15, at 108, 111. See infra note 43 and Figure 1.

[31]. See Supreme Court Biographies, https://supremecourt.gov/about /biographies.aspx.

[32]. See infra note 43 and Figure 1.

[33]. See Li Zhou, Trump Has Gotten 66 Judges Confirmed This Year. In His Second Year, Obama Had Gotten 49, Vox (Dec. 27, 2018, 7:10 AM), https://www.vox.com/2018/12/27/18136294/trump-mitch-mconnell-republican-judges [https://perma.cc/4ZV8-23K9]; see also Catherine Lucey & Meghan Hoyer, Trump Choosing White Men as Judges, Highest Rate in Decades, Chi. Trib. (Nov. 13, 2017, 6:22 PM), https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/politics/ct-trump-blacks-judges-20171113-story.html [https://perma.cc/9PKF-YDZA] (quoting Bush II’s Attorney General, Alberto Gonzalez, saying that Bush II pointedly requested that the number of women and minority judicial nominees be increased).

[34]. Stubbs, supra note 15, at 111. Given the dramatic increase in the appointment of women judges by Bush I relative to Reagan, Bush II only increased the share of women judges he appointed by 15 percent over Bush I. Id.

[35]. See Zhou, supra note 33.

[36]. See Stubbs, supra note 15, at 109.

[37]. Perhaps Obama’s failure to expressly affirm his commitment to judicial diversity can be explained by the research showing that women and minorities suffer negative consequences, relative to their white male peers, from exhibiting diversity-valuing behavior. See David R. Hekman et al., Does Diversity-Valuing Behavior Result in Diminished Performance Ratings for Non-White and Female Leaders?, 60 Acad. Mgmt. J. 771 (2017).

[38]. Stubbs, supra note 15, at 109, 111.

[39]. Id.

[40]. Obama’s first Supreme Court nominee was Sonia Sotomayor, whom he nominated in 2009 to replace retiring Justice David Souter. Obama’s second Supreme Court nominee was Elena Kagan, whom he nominated in 2010 to replace retiring Justice John Paul Stevens. See Supreme Court Biographies, supra note 31.

[41]. Reagan’s appointee, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor retired from the bench in 2006 during Bush II’s second term. See Ron Elving, The Fall of Harriett Miers: A Cautionary Tale for Dr. Rony Jackson, NPR (Mar. 30, 2018, 10:37 AM), https://www.npr.org/2018/03/30/598115811/the-fall-of-harriet-miers-a-cautionary-tale-for-dr-rony-jackson [https://perma.cc/542K-VD22]. Although Bush II initially nominated Harriet Mier, another woman, to replace O’Connor, her nomination was eventually withdrawn. Id. Ultimately, Bush II nominated, and the senate confirmed, Samuel Alito to replace Justice O’Connor, leaving Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg as the sole woman on the Supreme Court when Obama assumed office. Id.

[42]. Stubbs, supra note 15, at 111.

[43]. Id.

[44]. Id.

[45]. See supra text accompanying notes 24, 29, 33.

[46]. Rorie Spill Solberg & Eric N. Waltenburg, Trump’s Judicial Nominations Would Put a Lot of White Men on Federal Courts, Wash. Post: Monkey Cage (Nov. 28, 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/11/28/this-is-how-trump-is-changing-the-federal-courts [https://perma.cc/8ZTC-93VH] (noting that Trump inherited approximately one hundred more judicial vacancies than his predecessors).

[47]. Rorie Solberg & Eric N. Waltenburg, Trump’s Judicial Appointments: More White, More Male, Corvallis Gazette Times (June 12, 2018), https://www.gazettetimes.com /opinion/editorial/trump-sjudicialappointments-more-white-more-male/article_5291126c-7ff4-5122-a860-8498773cdc1b.html [https://perma.cc/J7YM-WKXV]. Trump has also appointed two Justices to the Supreme Court, filling nearly a quarter of those nine seats as well. Both of these appointees (Justice Neil Gorsuch to replace Justice Antonin Scalia in 2017 and Justice Brett Kavanaugh to replace Justice Anthony Kennedy in 2018) have been white men. See supra note 1.

[48]. See Carrie Johnson & Renee Klahr, Trump Is Reshaping the Judiciary: A Breakdown By Race, Gender and Qualification, NPR (Nov. 15, 2018, 5:00 AM), https://www.npr.org/2018/11/15/667483587/trump-is-reshaping-the-judiciary-a-breakdown-by-race-gender-and-qualification [https://perma.cc/5LZG-KAUJ].

[49]. Russell Wheeler, Appellate Court Vacancies May Be Scarce in Coming Years, Limiting Trump’s Impact, The Brookings Inst.: FixGov (Dec. 6, 2018), https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2018/12/06/trump-impact-on-appellate-courts [https://perma.cc/X46G-EN5P]; see also Tessa Berenson, President Trump Appointed Four Times as Many Federal Appeals Judges as Obama in His First Year, Time (Dec. 15, 2017), http://time.com/5066679/donald-trump-federal-judges-record [https://perma.cc/XV4U-T3SV]. According to at least one source, this record-setting pace of appointments for circuit court judges can be contrasted with his appointment of district court judges, which has lagged that of his predecessors to date. Joan Biskupic, Trump Fast-Tracks Appeal Judges, but Lags on Lower Courts, CNN: Politics (May 25, 2018, 6:16 AM), https://cnn.com/2018/05/25/politics/appeals-district-court-trump/index.html [https://perma.cc/CC55-XJK9].

[50]. During his campaign, Trump often proclaimed his commitment to nominating originalists judges in the mold of the late Justice Antonin Scalia. See Johnson & Klahr, supra note 48. For a discussion of the relationship between originalism and conservatism, see Keith Whittington, Is Originalism Too Conservative?, 34 Harv. J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 29 (2011).

[51]. Johnson & Klahr, supra note 48 (observing that while all presidents have appointed judges ideologically, only Trump has reversed the recent trend towards greater judicial diversity). See also Jennifer Bendery, Trump Is Remaking the Courts in His Image: White, Male and Straight, Huffington Post (Mar. 11, 2018, 9:08 AM), https://www.huffpost.com/entry/trump-judicial-nominees-white-male-straight_n_5aa2b9bee4b07047bec6107c [https://perma.cc/R8HY-82XW]; Richard Wolf, Trump’s 87 Picks To Be Federal Judges Are 92% White With Just One Black and One Hispanic Nominee, USA Today (Feb. 13, 2018, 3:26 PM), https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2018/02/13/trumps-87-picks-federal-judges-92-white-just-one-black-and-one-hispanic-nominee/333088002 [https://perma.cc/7ET4-5MF2]; Lucey & Hoyer, supra note 33.

[52]. See Biographical Directory of Article III Federal Judges, 1789–present, Fed. Jud. Ctr., https://www.fjc.gov/history/judges/search/advanced-search (last visited Jan. 23, 2019).

[53]. See supra note 44 and accompanying text.

[54]. Bush II’s judicial appointees were slightly less gender diverse than Trump’s (22 versus 24 percent), but significantly more racially diverse than Trump’s (18 versus 8 percent). Stubbs, supra note 15, at 111. See Solberg & Waltenburg, supra note 47 (observing that while both Republican and Democratic presidents appoint ideological judges, only Trump has reversed the modern presidential trend towards greater judicial diversity). But cf. Kevin R. Johnson, How Political Ideology Undermines Racial and Gender Diversity in Federal Judicial Selection: The Prospects for Judicial Diversity in the Trump Years, 2017 Wis. L. Rev. 345 (2017) (arguing that Trump’s commitment to appointing conservative judges would undermine judicial diversity).

[55]. See Stubbs, supra note 15, at 111.

[56]. Id.

[57]. See Biographical Directory of Article III Federal Judges, supra note 52 and accompanying text. According to data from the Federal Judicial Center, Trump has appointed approximately eighty-three federal judges, fifty-eight of them white males (79 percent), eighteen white females (22 percent), and seven minorities (8 percent). See id.

[58]. Although not the focus here, it is also notable that reports suggest that Trump’s judicial nominees have not included a single person who identifies as LGBT or who is disabled. Solberg & Waltenburg, supra note 47. On this point, however, Trump is indistinguishable from his Republican presidential predecessors, none of whom appointed an LGBT judge to the federal bench. See Carl W. Tobias, President Donald Trump and Federal Bench Diversity, 74 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. Online 400, 406–07 (2018) (acknowledging that Reagan, Bush I, nor Bush II appointed an LGBT judge to the federal bench).

[59]. See Johnson & Klahr, supra note 48. In his first two years, Trump has appointed only one African American and one Hispanic to the federal district courts. See John Gramlich, Trump Has Appointed a Larger Share of Female Judges Than Other GOP Presidents, But Lags Obama, Pew Research Center: Fact Tank (Oct. 2, 2018), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/10/02/trump-has-appointed-a-larger-share-of-female-judges-than-other-gop-presidents-but-lags-obama/ [https://perma.cc/P2KP-TC9C] (reporting that 90 percent of Trump’s appointees are white). For a demographic profile of sitting federal judges, including the percentage of black and Hispanic sitting federal judges, see Biographical Directory of Article III Federal Judges, supra note 52.

[60]. In eight instances Trump has appointed a judge who decreased the diversity of the bench. Rorie Solberg & Eric N. Waltenburg, Trump’s Presidency Marks the First Time in 24 Years That the Federal Bench Is Becoming Less Diverse, The Conversation (June 11, 2018, 6:43 AM), https://theconversation.com/trumps-presidency-marks-the-first-time-in-24-years-that-the-federal-bench-is-becoming-less-diverse-97663 [https://perma.cc/

V8BG-KFTU]. See also McMillion, supra note 15, at 5, 7, 16, 19 (showing a decline in the number of women and minority sitting judges, except Asian Americans, on the circuit court during Trump’s first year and a comparable decline in the number of women and minority sitting judges on the district court during Trump’s first year in office).

[61]. Solberg & Waltenburg, supra note 60.

[62]. Id.

[63]. Nearly 21 percent of Trump’s judicial nominees have decreased the diversity of the federal bench, compared to only 9 percent of Obama’s nominees, and an even smaller percentage for every president before Obama. Id. By comparison, only about 21 percent of Trump’s nominees have increased the diversity of the federal bench, which is only slightly higher than Reagan’s 18 percent and far lower than any of his other Republican presidential predecessors, including Bush II (34 percent) and Bush I (32 percent). Id.

[64]. This critique occurs across a wide range of contexts. See e.g. Richard H. Sander and Stuart Taylor, Jr., Mismatch: How Affirmative Action Hurts Students It’s Intended to Help and Why Universities Won’t Admit It (2012) (higher education admissions); Richard H. Sander, The Racial Paradox of the Corporate Law Firm, 84 N.C. L. Rev. 1755 (2006) (employment). In the judicial nominations context in particular, conservative critics assert that because there are so few minorities among potential conservative nominees, the attention to judicial diversity would come at the expense of selecting the most qualified candidates. See Tobias, supra note 58, at 414.

[65]. White House officials have asserted that Trump is prioritizing qualifications over diversity. See Lucey & Hoyer, supra note 33.

[66]. See Zhou, supra note 33. See also supra text accompanying note 57. Trump’s six judicial nominees deemed “not qualified” by the ABA exceeds the number of such nominees by any other president in the first two years of office. Id. (citing the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights); Carlos Ballesteros, Trump is Nominating Unqualified Judges at an Unprecedented Rate, Newsweek (Nov. 17, 2017, 12:11 PM), https://www.newsweek.com/trump-nominating-unqualified-judges-left-and-right-710263 [https://perma.cc/UX5T-2JT5]. According to data from the Congressional Research Service, Trump is the only one of his recent presidential predecessors to nominate a circuit court judge rated “not qualified” by the American Bar Association and had both the highest number and percentage of district court nominees rated “not qualified” during his first year in office. See McMillion, supra note 6, at 14–15.

[67]. See infra Part IV. This is to say nothing of Trump’s second Supreme Court appointee, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who was embroiled in his own weeks-long scandal concerning allegations of sexual misconduct. Investigation of these allegations by the senate Judiciary Committee caused a delay in his confirmation process during which some argued that, irrespective of the truth of the allegations against him, Kavanaugh displayed a temperament unbefitting the highest judicial office. See Robert Barnes, As Kavanaugh Is All but Confirmed, Questions Linger About His Judicial Temperament, Wash. Post (Oct. 5, 2018), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/courts_law/as-kavanaugh-is-all-but-confirmed-questions-linger-about-his-judicial-temperament/2018/10/05/998da822-c8c4-11e8-9b1c-a90f1daae309_story.html [https://perma.cc/Q2SV-LV4S].

[68]. Numerous scholars have noted the relationship between diversity and judicial legitimacy. See, e.g., Kevin R. Johnson & Luis Fuentes-Rohwer, A Principled Approach to the Quest for Racial Diversity on the Judiciary, 10 Mich. J. Race & L. 5 (2005); Sylvia R. Lazos Vargas, Does a Diverse Judiciary Attain a Rule of Law That Is Inclusive?: What Grutter v. Bollinger Has To Say About Diversity on the Bench, 10 Mich. J. Race & L. 101 (2004); Scherer, supra note 24, at 625. See also Stacy L. Hawkins, Batson for Judges, Police Officers & Teachers: Lessons in Democracy from the Jury Box, 23 Mich. J. Race & L.1(2017).

[69]. On average, Trump’s judicial appointees have been relatively young, making it likely that they will serve on the bench for the next thirty or even forty years. See Solberg & Waltenburg, supra note 46. For a discussion of the difficulty of reversing past judicial trends, see Stubbs, supra note 15, at 94.

[70]. See supra text accompanying notes 52–53. See also infra text accompanying note 95.

[71]. See supra text accompanying note 50.

[72]. This campaign slogan embodies dog whistle politics. This appeal to white racial identity politics cloaked in the rhetoric of populism featured prominently in Barry Goldwater’s 1964 failed presidential bid and was carried forward by successive Republican presidents, including by Richard Nixon in both his 1968 and 1972 presidential bids, as part of the Republican party’s attempt to appeal to white Southern Democrats. See Ian Haney Lopez, Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class 19–27 (2013). Given shifts in the political geography, this appeal no longer resonates exclusively with Southern whites, but has broader appeal among a particular segment of the white electorate. Id.

[73]. Exec. Order No. 13769, 3 C.F.R. 272 (2018). During his presidential campaign, Trump described the ban as “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.” Richard Wolf, Travel Ban Lexicon: From Candidate Trump’s Campaign Promises to President Trump’s Tweets, USA Today (Apr. 24, 2018, 11:41 AM), https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2018/04/24/travel-ban-donald-trump-campaign-promises-president-tweets/542504002 [https://perma.cc/MHZ8-WSRA].

[74]. Sheryl Gay Stolberg & Michael Tackett, Trump Suggests Government Shutdown Could Last for ‘Months or Even Years’, N.Y. Times (Jan. 4, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com /2019/01/04/us/politics/democrats-trump-meeting-government-shutdown.html [https://perma.cc/E8LB-YQ8U]. Most recently, in the face of congressional denial of funding to build the border wall, the president has invoked executive authority to declare a national emergency in order to build the promised border wall with Mexico. See Declaring a National Emergency Concerning the Southern Border of the United States, 84 Fed. Reg. 4949 (Feb. 15, 2019).

[75]. See, e.g., Nick Miroff, Scanning Immigrants’ Old Fingerprints, U.S. Threatens to Strip Thousands of Citizenship, Wash. Post (June 13, 2018), https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/scanning-immigrants-old-fingerprints-us-threatens-to-strip-thousands-of-citizenship/2018/06/13/2230d8a2-6f2e-11e8-afd5-778aca903bbe_story.html?utm_term=.f2a43eddb377 [https://perma.cc/QK6B-H7FN]. The reference to the “browning of America” is often attributed to William Frey’s analysis of future demographic trends. See William H. Frey, Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics Are Remaking America (2015).

[76]. One such reference was widely-reported in the media because of Trump’s profane reference to immigrants from African nations as “people from shithole countries.” E.g., Josh Dawsey, Trump Derides Protections for Immigrants From ‘Shithole’ Countries, Wash. Post (Jan. 12, 2018), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-attacks-protections-for-immigrants-from-shithole-countries-in-oval-office-meeting/2018/01/11/bfc0725c-f711-11e7-91af-31ac729add94_story.htmlutm_term=.473fbdca245d [https://perma.cc/62AK-ZCRB]. By contrast, Trump has said we should encourage immigration from certain white, European countries, such as Norway. Id.

[77]. It is no coincidence that Trump’s immigration policy has targeted precisely those ethnic groups that have represented the largest growth in immigration over the last decade. See Frey, supra note 75, at 149–66 (2015).

[78]. See supra notes 73–74.

[79]. See Heidi Beirich, Rage Against Change: White Supremacy Flourishes Amid Fears of Immigration and Nation’s Shifting Demographics, Intelligence Rep., Spring 2019, at 35, https://www.splcenter.org/sites/default/files/intelligence_report_166.pdf [https://perma.cc/6GRX-AGGG] (attributing a rise in white hate groups at least in part to Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric and polarizing policies on issues of race and immigration).

[80]. Several people who have held positions of influence in Trump’s Administration have been associated with white supremacists and/or white nationalist groups, including Steve Bannon, Michael Anton, Sebastian Gorka, and Stephen Miller. See Louis Jacobson, Are There White Nationalists in the White House?, Politifact (Aug. 15, 2017, 4:47 PM), https://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/article/2017/aug/15/are-there-white-nation

alists-white-house [https://perma.cc/S7KJ-CGTA]; see also Hate in the White House, Intelligence Rep., Spring 2019, at 14 https://www.splcenter.org/sites/default/files/intelligence_report_166.pdf [https://perma.cc/6GRX-AGGG] (cataloguing White House connections to alt-right organizations and other hate groups).

[81]. See Michael D. Shear & Maggie Haberman, Trump Defends Initial Remarks on Charlottesville; Again Blames ‘Both Sides’, N.Y. Times (Aug. 15, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/15/us/politics/trump-press-conference-charlottesville.html [https://perma.cc/WML4-R84L]; see also Full Text: Trump’s Comments on White Supremacists, ‘Alt-Left’ in Charlottesville, Politico (Aug. 15, 2017, 6:16 PM), https://www.politico.com/story/2017/08/15/full-text-trump-comments-white-supremacists-alt-left-transcript-241662 [https://perma.cc/AHC8-Z3SH].

[82]. See Beirich, supra note 79. For a discussion of dog whistle politics, see Lopez, supra note 72.

[83]. See, e.g., Abed Ayoub & Khaled Beydoun, Executive Disorder: The Muslim Ban, Emergency Advocacy, and the Fires Next Time, 22 Mich. J. Race & L. 215, 221 (2017) (describing Trump’s campaign as “‘racism summits,’ [that] offered a glimpse of the country the candidate promised and hoped to deliver”); Josh Chafetz & David E. Pozen, How Constitutional Norms Break Down, 65 UCLA L. Rev. 1430, 1451 (2018) (describing Trump as “wink[ing] at white supremacists”); Henry A. Giroux, White Nationalism, Armed Culture and State Violence in the Age of Donald Trump, 43 Phil. & Soc. Criticism 887, 890 (2017); Lindsay Pérez Huber, “Make America Great Again!”: Donald Trump, Racist Nativism, and the Virulent Adherence to White Supremacy Amid U.S. Demographic Change, 10 Charleston L. Rev. 215 (2016); Christopher N. Lasch, Sanctuary Cities and Dog-Whistle Politics, 42 New Eng. J. on Crim. & Civ. Confinement 159 (2016); Matthew R. Segal, Civil Rights and State Courts in the Trump Era, 12 Harv. L & Pol’y Rev. 49 (2018). See also Jamelle Bouie, What We Have Unleashed, Slate (June 1, 2017, 7:59 PM), https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2017/06/this-years-string-of-brutal-hate-crimes-is-intrinsically-connected-to-the-rise-of-trump.html [https://perma.cc/E3YU-MJXK]; Mirren Gidda, How Donald Trump’s Nationalism Won Over White Americans, Newsweek (Nov. 15, 2016, 3:00 AM), https://www.newsweek.com/donald-trump-nationalism-racism-make-america-great-again-521083 [https://perma.cc/5L7U-SQ9P]; Jamie Kizzire et al., America the Trumped: 10 Ways the Administration Attacked Civil Rights in Year One, S. Poverty L. Ctr. (Jan. 19, 2018), https://www.splcenter.org/20180119/america-trumped-10-ways-administration-attacked-civil-rights-year-one [https://perma.cc/GZP2-R4BD]; Alexis Okeowo, Hate on the Rise After Trump’s Election, New Yorker (Nov. 17, 2016), https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/hate-on-the-rise-after-trumps-election [https://perma.cc/G3TA-4CZZ].

[84]. See Lopez, supra note 72 (describing the Southern Strategy and Barry Goldwater’s failed presidential bid in 1964).

[85]. See Hugh Hewitt, Trump’s Massive Impact on the Federal Bench, Wash. Post (May 22, 2018), https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/trumps-massive-impact-on-the-federalbench/2018/05/22/d440a614-5dcf-11e8-a4a4-c070ef53f315_story.html?utm_term=.a055655d96fc [https://perma.cc/BU82-LE63].

[86]. See supra text accompanying note 43.

[87]. William M. Landes & Richard A. Posner, Rational Judicial Behavior: A Statistical Study, 1 J. Legal Analysis 775, 782 (2009) (ranking Justice Clarence Thomas as the most conservative Justice on the Court for the period 1937–2006).

[88]. See infra Part IV.

[89]. See Kim Parker, Nikki Graf, & Ruth Igielnik, Generation Z Looks a Lot Like Millennials on Key Social and Political Issues, Pew Res. Ctr. (Jan. 17, 2019), https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2019/01/17/generation-z-looks-a-lot-like-millennials-on-key-social-and-political-issues [https://perma.cc/SE6P-Z3FK] (reporting that two-thirds of post-millennials, millennials and Gen Xers, ranging in age from 17–54, support more women running for office, as do nearly two-thirds of baby boomers).

[90]. See supra note 68; see also Stubbs, supra note 15.

[91]. This is based on a snapshot of the federal judiciary as of March 10, 2016. See id. at 117.

[92]. Quick Facts: United States, U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045218 [https://perma.cc/ZK4U-WQ2E]. The profession has also been diversifying, but it is also less diverse than the general population. See ABA National Lawyer Population Survey, Am. B. Ass’n, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/market_research/National_Lawyer_Population_Demographics_2008-2018.pdf [https://perma.cc/SU6X-2GYF] (showing female representation currently at 36 percent of the profession and minority representation at 15 percent).

[93]. See supra Part I.

[94]. See Biographical Directory of Article III Federal Judges, supra note 52.

[95]. These trends have been on the horizon for decades. See generally Frey, supra note 75. Already in the United States there are several majority minority states and forty-two of the nation’s one hundred largest metropolitan areas are majority minority. Id.at157.

[96]. Richard Fry & Kim Parker, Early Benchmarks Show ‘Post–Millennials’ on Track to Be Most Diverse, Best-Educated Generation Yet, Pew Res. Ctr. (Nov. 15, 2018), https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/11/15/early-benchmarks-show-post-millennials-on-track-to-be-most-diverse-best-educated-generation-yet [https://perma.cc/XR38-WQG5].

[97]. A related Pew Research Center study of political and social attitudes among younger generations finds that nearly two-thirds of both post–millennials and millennials believe “increased racial and ethnic diversity is a good thing for society” and a similar share of both believe the increased number of women running for political office is a “good thing.” See Parker, Graf, & Igielnik, supra note 89.

[98]. Id.

[99]. Reflective Democracy 2017 Voter Opinion Research, Reflective Democracy Campaign (Oct. 2017), https://wholeads.us/resources/for-activists [https://perma.cc/9M5G-D4UV].

[100]. Id. at 6. Fifty-two percent of all respondents said there are too many white men in office. Fifty-one percent and 43 percent, respectively, thought there are too few women and too few minorities in office. Id. Although there were wide partisan gaps in response rates, a third of Republicans agreed there are too few women in office and nearly a quarter agreed there are too few minorities in office. Id. at 7.

[101]. Id. at 19–21. Here the partisan differences were less stark. More than nine in ten (92 percent) Democrats and almost two-thirds (65 percent) of Republicans expressed support for efforts to increase the number of women in office and nearly nine in ten (88 percent) Democrats and over half (57 percent) of Republicans expressed support for efforts to increase minorities in office. Id.

[102]. See Supreme Court Biographies, supra note 31.

[103]. See id.

[104]. Maureen Linke, Just How Diverse Is the New Congress, Wall St. J. (Nov. 15, 2018, 7:30 AM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/just-how-diverse-is-the-new-congress-1542285001 [https://perma.cc/3J8Y-W7YT] (observing historic representation in the 116th Congress of women, African Americans and Hispanics, as well as the first Native American (2) and Muslim (2) women to serve in congress).

[105]. See, e.g., Stacy Hawkins, Diversity, Democracy & Pluralism: Confronting the Reality of Our Inequality, 66 Mercer L. Rev. 577, 578 (2015) (discussing notable political firsts).

[106]. See supra notes 24, 29, and 33 (discussing President Carter, Clinton, and Bush II’s express acknowledgment of the importance of judicial diversity). Moreover, Obama’s commitment to judicial diversity is evident in the records he broke with his judicial appointments. See Stubbs, supra note 15, at 108–09.

[107]. See supra note 68. See also Stubbs, supra note 15, 119–24 (surveying the scholarship on judicial diversity); Mark S. Hurwitz & Drew Noble Lanier, Diversity in State and Federal Appellate Courts: Change and Continuity Across 20 Years, 29 Just. Sys. J. 47, 49 (2008) (discussing the scholarly literature on judicial diversity and its benefits for improved judicial legitimacy and effective judicial decisionmaking).

[108]. Hiroshi Fukurai & Darryl Davies, Affirmative Action in Jury Selection: Racially Representative Juries, Racial Quotas, and Affirmative Juries of the Hennepin Model and the Jury De Medietate Linguae, 4 Va. J. Soc. Pol’y & L. 645, 663–64 (1997) (demonstrating that respondents rated racially and ethnically diverse juries as “more fair” than all white juries).

[109]. Id. See also Nancy Scherer & Brett Curry, Does Descriptive Race Representation Enhance Institutional Legitimacy? The Case of the U.S. Courts, 72 J. Pol. 90, 98–100 (2010) (discussing empirical analysis showing greater support for judicial legitimacy among blacks when there are more black judges on the bench. Notably, this enhanced legitimacy was not registered for whites, but whites displayed a much higher baseline for judicial legitimacy than blacks).

[110]. Examples abound, but include for instance the Scottsboro Boys, five young black men who were wrongly convicted in the 1930s by an all-white jury of raping and murdering a white woman. See Jeffrey Abramson, We, the Jury: The Jury System and the Ideal of Democracy 111 (1994) (citing noted Swiss sociologist Gunnar Myrdal, who described this phenomenon as “an extreme form of democracy” that favors only the interests of the majority).

[111]. The most prominent example is the Rodney King trial, in which several white police officers were acquitted of brutally beating a black motorist in Los Angeles in 1992. See Fukurai & Davies, supra note 108, at 646.

[112]. See Johnson & Fuentes-Rohwer, supra note 68, at 6 (observing about the justice system that “no rebuke stings more than the concise statement that an ‘all-White jury’ convicted a [b]lack defendant”).

[113]. The theory of procedural justice, which has been empirically demonstrated, posits that citizens are more likely to accord legitimacy to judicial decisions when they result from fair processes, irrespective of the substantive result. See Tracey L. Meares & Tom R. Tyler, Justice Sotomayor and the Jurisprudence of Procedural Justice, 123 Yale L.J. F. 525 (2014).

[114]. See Scherer, supra note 24, at 625.

[115]. See e.g., Meares & Tyler, supra note 113; Tom R. Tyler, Governing Amid Diversity: The Effects of Fair Decisionmaking Procedures on the Legitimacy of Government, 28 L. & Soc’y Rev. 809 (1994). For a discussion of this phenomenon as it relates to judging in particular, see Hawkins, supra note 68, at 8. See also Scherer & Curry, supra note 109, at 90–91 (“[L]itigants’ satisfaction with the resolution of their legal dispute was largely influenced by the fairness of the process, rather than the substantive outcome of the dispute.”).

[116]. See Tracey L. Meares, The Good Cop: Knowing the Difference Between Lawful or Effective Policing and Rightful Policing—And Why It Matters, 54 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1865 (2013).

[117]. Studies have shown that a significant majority of respondents of all races (67 percent) believe diverse juries are more fair than single race juries, with minority respondents expressing this belief at an even higher rate (75 percent of Hispanics and 92 percent of blacks). See Fukurai and Davies, supra note 108, at 663. Although the data cited here refers to juries as judicial decisionmakers, there is no reason to believe the same would not apply equally to judges as judicial decisionmakers.

[118]. See supra note 97 and accompanying text (discussing consensus among millennials and post–millennials about the need for greater diversity in elected government).

[119]. See Hawkins, supra note 68, at 13, 45 (discussing the jury de medietate linguae and its origins in early American common law as a means to diversify juries, as well as passage of the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 committing the federal government to diversity in public employment until the civil service “looks like America.”).

[120]. Stubbs, supra note 15, at 109.

[121]. See id.

[122]. See supra text accompanying note 24.

[123]. See supra text accompanying note 42.

[124]. See Demography of Article III Judges, 1789–2017, Fed. Jud. Ctr., https://www.fjc.gov/history/exhibits/graphs-and-maps/race-and-ethnicity (last visited Apr. 11, 2019).

[125]. For a fuller discussion of this evidence, see Hawkins, supra note 68, at 27–30.

[126]. Id.

[127]. See Pat K. Chew & Robert E. Kelley, Myth of the Color-Blind Judge: An Empirical Analysis of Racial Harassment Cases, 86 Wash. U. L. Rev. 1117, 1134 (2009).

[128]. See Adam B. Cox & Thomas J. Miles, Judging the Voting Rights Act, 108 Colum. L. Rev. 1, 45 (2008) (finding white circuit court judges were significantly more likely to rule in favor of minorities in voting rights cases when they sat on a panel with an African American judge than when they sat on an all-white panel). See also Stubbs, supra note 15, at 119–24 (discussing the research on how diversity improves judicial decisionmaking).

[129]. See Lazos Vargas, supra note 68 (examining the impact of the Supreme Court’s composition on the rule of law and suggesting greater diversity on the Court has resulted and would result in greater civil rights for minorities).

[130]. African American judges nominated by both Democrats (47 percent) and Republicans (43 percent) ruled in favor of black plaintiffs in discrimination cases significantly more often than white judges nominated by either Democrats (27 percent) or Republicans (17 percent). Chew & Kelley, supra note 127, at 1149.

[131]. See Abramson, supra note 110, at 131 (“[T]he appearance of justice can[not] be delivered by a . . . process that continually underrepresents minorities.”).

[132]. See Hawkins, supra note 68, at 7–9 (discussing the importance of trust to the effective functioning of our democratic institutions and the impact of continual political losses on that trust).

[133]. See supra text accompanying notes 52, 92.

[134]. See supra text accompanying notes 97–101.

[135]. See supra text accompanying notes 59–63.