Introduction

Over the past thirty years, legal scholars have created a robust literature on the relationship between the practices of lawyers and social movements in advocating for social change.1 This literature resulted in part from the critique of lawyer-led social change by academics worried about the institutional inability of courts to address social problems2 and the fear of backlash if courts took the initiative away from social movements in addressing systemic injustice.3 In response to these criticisms, the legal profession has increasingly encouraged public interest lawyers to engage with social movements and emphasized grassroots, client-led advocacy over appellate legal strategy.4 At the same time, critics of law-and-organizing approaches to public interest advocacy have emphasized both the possibility that lawyers will demobilize community activists by virtue of their very involvement, and that lawyers will both dominate and be unable to appropriately navigate the conflicting priorities within social movements.5

In this article, we place the legal and organizing work of the Los Angeles Center for Community Law and Action (LACCLA) within this theoretical context and apply it to the tenant movement emerging in southern California, as understood by the members of LACCLA as well as organizers and activists such as the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP). This article primarily discusses how low-income tenants, lawyers, and community organizers have worked together to build a tenants’ rights movement in southern California. This article goes on to explore critiques of the housing rights movements’ policy priorities both procedurally (are the right voices prioritized?) and substantively (are the right policies being advocated?).

I. Case Study: The Los Angeles Center for Community Law and Action as a Law and Organizing Model

The Los Angeles Center for Community Law and Action (LACCLA) is an east Los Angeles-based nonprofit dedicated to supporting members of the community through collective action and legal representation, thereby empowering the community to exercise its social, economic, and political power.6 In contrast to what some ethics professors have characterized as the “hired gun” or “atomistic” model of traditional lawyering – zealously representing individual clients within the scope of a legal dispute7—LACCLA’s method combines organizing, leadership training, public action, and strategic legal representation to combat exploitative and discriminatory economic practices.

A. Identifying Tenant Protections as a Community Priority

In practice, LACCLA empowers members through regular community meetings organized primarily for Spanish-speaking residents of east8 Los Angeles facing displacement and eviction. Meetings are held in Spanish at Saint Mary’s Catholic Church in Boyle Heights on Saturday evenings. While some organizations directly target legal structures as a focus of social change through movement politics,9 LACCLA does not view changing particular laws or policies as its goal. Instead, LACCLA focuses on building community power by creating spaces where low-income and traditionally marginalized people can discuss issues and identify opportunities for collective action and social transformation. The membership of LACCLA itself then decides which campaigns LACCLA will get involved in and what the scope of LACCLA’s involvement will be.

To take one example, LACCLA is currently involved in the push to expand tenant protections, including rent control and just cause eviction standards to residents who live in unincorporated LA County. In 2015, LACCLA was primarily working with homeowners facing post-foreclosure eviction. However, due to rising rents and other economic pressures, residential tenants facing eviction increasingly dominated attendance at Saturday meetings and LACCLA events. In particular, LACCLA saw a large influx of tenants from unincorporated East Los Angeles, just a few blocks east of Saint Mary’s Catholic Church where LACCLA operates. Unlike tenants who live in incorporated Los Angeles, where Saint Mary’s is located, tenants who lived across the municipal border had no legal protection when faced with large rent increases and mass “no fault” evictions. This influx of residential tenants from unincorporated East Los Angeles observed a consistent pattern in which corporate landlords and other investors: (1) purchased what had previously been family-owned rental properties, (2) dramatically increased the rent (60 to 400 percent) or issued “no fault” eviction notices,10 (3) evicted the existing tenants (predominantly low-income and Latino), (4) converted the units to luxury apartments, and (5) replaced those tenants with higher-income tenants.11

In response to these observations, LACCLA members asked LACCLA attorneys to identify potential laws, including rent control, that could be changed to prohibit these practices. LACCLA attorneys reported that the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors was the most local level of government that could pass legislation affecting East Los Angeles, and that both rent control and just cause eviction protections would be necessary to prevent corporate landlords from engaging in these practices. LACCLA members then organized and planned a march to the office of Hilda Solis, the Supervisor who represents East Los Angeles, to demand that the Supervisors take action on this issue.12 Five days later, the Board of Supervisors voted to study the issue and create a working group to investigate possible tenant protections in unincorporated areas.13 In August, the working group commissioned by the Board of Supervisors voted overwhelmingly to recommend that the Board pass strong just cause and rent control ordinances.14

B. Legal Representation in Support of the Tenants’ Rights Movement

Sameer Ashar’s study of movement lawyers assisting worker centers in New York City found that movement lawyering activities could be broken down into three types of tasks: (a) claim-centered legal work, (b) organizing-centered legal work, and (c) policy advocacy-centered legal work.15 Claim-centered work in housing litigation can be defined as legal advocacy with the aim of winning traditional legal objectives for individuals or groups of tenants, such as preventing eviction or obtaining repairs to uninhabitable apartments. Organizing-centered work can be defined as legal work that promotes and defends tenant organizing and the tactical use of direct action to achieve movement objectives, such as preventing landlords from disrupting tenant protests or protecting the confidentiality of organizers and activists. Policy-centered work can be defined as conducting legal analysis, drafting reports and petitions, and pressuring government agencies and elected officials to obtain movement objectives. LACCLA is currently engaging in work in all three of these categories to push forward movement goals regarding rent control and just cause eviction protections.

(1) Claim-Centered Legal Work

LACCLA’s Saturday legal clinics at Saint Mary’s Catholic Church constitute the bulk of its claim-centered legal work. At these clinics, LACCLA provides free consultations to walk-in clients who are interested in participating in the membership activities of LACCLA. LACCLA will often take these individuals on as “full representation” clients. Because of the high volume of residential tenants attending LACCLA meetings, this typically means that LACCLA is representing these tenants for free in eviction proceedings or suing a tenant’s landlord, affirmatively seeking injunctive relief from breaches of the warranty of habitability, tenant harassment, or illegal rent increases.

(2) Organizing-Centered Legal Work

LACCLA also provides legal services directly to other community organizations in support of their organizing work. In particular, LACCLA represents residential tenant associations when a building chooses to organize collectively to push back against an unfair or unlawful landlord practice or seek to collectively bargain a new lease agreement, typically in the face of a large rent increase. LACCLA additionally provides in-court representation to protestors when landlords seek injunctions prohibiting tenant protest or sues tenant protestors for defamation. For example, in the “Mariachi” cases, an investor purchased a large residential property in Mariachi Plaza, a historic center of Latino culture in east Los Angeles, and raised the rent 80 percent in an attempt to convert the building into luxury housing.16 LACCLA successfully represented the Los Angeles Tenants Union and assisted the association of “Mariachi” tenants in negotiating a collective bargaining agreement with the investor that limited rent increases to a one-time 14-percent increase, with subsequent rent increases capped to follow the Los Angeles Rent Stabilization Ordinance over the term of the agreement, and mandatory collective bargaining at the expiration of the four-year agreement.17

(3) Policy Advocacy-Centered Legal Work

LACCLA’s policy-centered advocacy over the last two years has focused primarily on the expansion of rent control and just cause eviction protections. While LACCLA has drafted policy papers and visited elected officials and their representatives directly, LACCLA has found that its direct actions, including marches and rallies as well as disrupting meetings and legislative proceedings, have been more effective at moving forward the legislative priorities identified by LACCLA members.

C. Challenges for a Movement-Centered Practice

Scott Cummings and Ingrid Eagly, in analyzing the challenges faced by lawyers employing law-and-organizing techniques, have identified practical and ethical difficulties that arise when lawyers participate in movement-centered legal representation. In particular, Cummings and Eagly describe resource constraints and role constraints in combining lawyering and community organizing, as well as ethical considerations regarding confidentiality, scope of representation, and conflicts of interest.18 Cummings has further commented that the rules of professional responsibility, which are designed to ensure ethical compliance for lawyers engaging in direct, one-on-one representation, can be easily manipulated by opponents of social movements to undermine legitimate legal activity.19 For example, landlords and local politicians have accused housing activists of intentionally misleading tenants into risking eviction or committing civil disobedience without informing them of the consequences of taking these actions.20

LACCLA resolves these tensions by making sure that, first and foremost, LACCLA members, and not lawyers and professional staff, are setting the priorities of the organization. For example, in expanding tenant protections to unincorporated Los Angeles County, it was East Los Angeles residents who identified the problem of large rent increases and proposed that LACCLA advocate for a rent control law similar to the law in effect in municipal Los Angeles in order to prevent the mass displacement of the Latino community of East Los Angeles. Whenever LACCLA represents a tenant association or collectively represents a group of tenants, LACCLA makes sure that tenants sign a conflicts waiver and specify how disputes between clients will be resolved if disputes arise.21

II. Case Study: The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project as a Policy Advocate

In December of 2017, LACCLA began a partnership with the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP), adding another layer of advocacy to the campaign for rent control in unincorporated Los Angeles County. AEMP is a data visualization, data analysis, and digital storytelling collective, documenting dispossession and resistance in gentrifying U.S. landscapes. AEMP performs research, gathers oral histories, and makes maps in partnership with housing justice organizations and communities directly impacted by real estate speculation. AEMP’s work has many purposes and uses: bearing witness, building community power, informing policy, and laying the groundwork for a radical vision. AEMP coalesced in 2013 in the wake of the Bay Area’s most recent housing crisis. Now doing work in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Alameda, Sacramento, and San Mateo counties, AEMP has produced over a hundred interactive digital maps, over a hundred oral histories and video pieces, six comprehensive and collaboratively produced reports, numerous community events, murals, zines, and more to contribute to building tenant power. To best understand eviction landscapes in each city in which it works, AEMP works directly with community members to elicit narratives and develop ways to visualize the impact that the housing crisis is having on California communities.

A. Identifying Tenant Protections as a Priority

AEMP’s research is done with and by tenants, and tenants have identified rent control and just cause as the policies tenants need to protect themselves from a turbulent, profit-seeking market and the incentivized displacement it depends upon. In solidarity with the tenants’ rights movement, AEMP has contributed to policy advocacy for rent control and just cause eviction protections to preserve affordable housing and protect tenants from displacement. These policies keep rents for tenants affordable and allow tenants to request repairs and refuse illegal rent increases without fear of a no-cause eviction.

The questions and conclusions that AEMP invokes in its work are conceived of collectively among AEMP members and in collaboration with its community partners. AEMP believes in the importance of employing what Kim Tallbear describes as “objectivity in action,” or inquiring not at a distance, but as situated within the spaces where AEMP does its work.22 As such, AEMP finds it important not to produce knowledge for impacted communities, but with those experiencing multifarious aspects of urban change. AEMP has made conscious decisions to curate and relate certain data sets together based on the analysis of its various partners, storytellers, and members.

(1) Centering Tenant Experiences in the California Housing Crisis

The primary data AEMP uses in guiding its work are firsthand interviews with impacted populations. Since 2013, AEMP’s Narratives of Displacement and Resistance Oral History Project has documented over one hundred interviews23 in the San Francisco Bay Area, and more recently in Los Angeles, that illuminate the following in cities across California: that tenants are being evicted at unacceptable rates, and cities’ Black, poor, and working-class communities are being forced out of the places they have made home. Carolina Rodriguez, LACCLA member, organizer, and contributor to AEMP’s Narratives of Displacement and Resistance oral history project, tells one such story here, informing the fight for tenant protections in unincorporated areas of Los Angeles County:

When I used to live [on Duncan Street] my landlord started raising my rent every year a hundred dollars. I went to go see if I had any rights or to try to do something about it. They told me that just because I lived in East LA and we didn’t have no rent control the landlords could do whatever they want. So what did I decide to do? I just moved out. . . . And I knew because of my previous [rental experience] that we didn’t have no rent control so we didn’t have no rights. So I knew that if I didn’t find a place I was going to end up in the streets with my kids. . . . [I subsequently moved to my current apartment in East Los Angeles.] And here, everything was fine until Winstar Properties bought the building. And they decided to raise my rent from $1250 to $2000. And, I was like, “Oh my god, how are we going to do another kicking us out? We can’t pay that. We can’t afford that. 24

Alongside firsthand narrative accounts, AEMP makes available public datasets, creating spatial representations of city and county records retrieved through record requests, surveyed data, along with census and demographic data to tell the various interlinked stories of urban dispossession and resistance in gentrifying areas. In May of 2018, with statewide renters’ rights organization Tenants Together, AEMP obtained previously unreleased data from the California Judicial Council, which aggregates data on eviction lawsuits in county courthouses across the state. AEMP found that, between 2014 and 2016, roughly half a million renters in California faced court eviction each year—three times what was previously estimated by researchers who did not have access to these primary source documents.25 AEMP estimates that, if it were able to track other forms of involuntary displacement, the number would be closer to a million tenants each year. With seventeen million renters in the state, this means one in seventeen renters are facing eviction every year. AEMP also found that 75 percent of court evictions are resolved within forty-five days, and 60 percent are resolved within one month.26 This process of being removed from one’s home, community, and support network, is happening at an extremely rapid rate, and it is a process that half a million renters are going through every year.

Similarly, in AEMP’s 2015 report with the Eviction Defense Collaborative, a nonprofit legal clinic in San Francisco that represents roughly 90 percent of tenants facing unlawful detainer cases in the city, AEMP found that Black and Latinx tenants were defendants in the majority of eviction cases, while White tenants were significantly less likely to be sued for eviction. Compared to San Francisco’s population in 2015, Black tenants were overrepresented as defendants by over 300 percent. White tenants made up only 17.3 percent of EDC’s total clientele, though they made up 41.4 percent of the city’s population at the time.28 Since the 1970s, San Francisco’s Black population has been cut in half, though the city’s population has grown during this time.29

III. Do Social Movements Set the Wrong Priorities?

One of the most pervasive critiques of social movement advocacy is that movement leadership misdiagnoses problems and therefore advocates for the wrong policy solutions. For example, in the classic essay, “Serving Two Masters,” Derrick Bell critiqued civil rights lawyers involved in the school desegregation campaign for focusing their advocacy on school integration rather than increasing resources for Black students, which lead to unenforceable judicial proclamations rather than realistically obtainable educational outcomes.30 While Bell argued that listening to individual clients rather than movement leaders would have led to better outcomes, in the housing context, critics of housing-movement activists often argue that the voices of professional real estate lawyers and economists, rather than the affected tenant population, should be given priority.31

While the real estate lobby argues that policy experts have reached a consensus against rent control, the academic debate is at worst mixed for tenant advocates.32 Some academics point to “welfare loss” that rent control policies generate, as rent control reduces tenant turnover and as landlords and developers destroy affordable housing to avoid rent control laws by converting rental apartments in to condos.33 Other experts contend that rent control benefits existing tenants without limiting new construction.34 Most importantly, claims that rent control ordinances are responsible for the rampant gentrification and displacement does not match experiences of vulnerable renters in California cities.35

Conclusion

A combination of law and organizing advocacy centers the priorities of traditionally marginalized people like working-class tenants. Given that tenants themselves have identified rent control and just cause eviction as a movement priority, should the housing rights movements abandon rent control as one of many solutions to California’s affordable housing crisis? Research and tenants’ experiences suggest that the answer is a resounding no. The legacy of housing activism in California, where rent control movements remain among the most celebrated tenants’ rights victories in history,36 further supports housing movements’ decisions to adopt and expand rent control as a central priority for movement work.

[1] See Sameer M. Ashar, Public Interest Lawyers and Resistance Movements, 95 Cal. L. Rev. 1879, 1906 (2007) (noting that the legal academy in the 1990s was beginning to examine a “new kind of resistance strategy, in which clients reversed the traditional power dynamic and led lawyers in advocacy efforts on the basis of their knowledge, dignity, and courage”); Scott L. Cummings & Ingrid V. Eagly, A Critical Reflection on Law and Organizing, 48 UCLA L. Rev. 443, 443 (2001) (noting that the 90s was a period of “lively debate” regarding the role of lawyers with respect to social change).

[2] See generally Gerald N. Rosenberg, The Hollow Hope: Can Courts Bring About Social Change? (2d ed. 2008).

[3] See generally Michael J. Klarman, From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality (2004).

[4] See, e.g., Lani Guinier & Gerald Torres, Changing the Wind: Notes Toward a Demosprudence of Law and Social Movements, 123 Yale L.J. 2740, 2740 (2014) (describing courses taught on the subject at Harvard, Yale, and the University of Texas regarding the practice of movement lawyering); Rebellious Lawyering 2018, https://reblaw.yale.edu/ (last visited Aug. 16, 2018) (announcing the speakers for and dates of the annual conference regarding movement lawyers);.

[5] Catherine Albiston, The Dark Side of Litigation as a Social Movement Strategy, 96 Iowa L. Rev. Bull. 61, 74 (2011) (noting that the involvement of lawyers in a social movement can change the goals and identity of the movement); Cummings & Eagly, supra note 1, at 490–516 (summarizing criticisms); see Guinier & Torres, supra note 4, at 2796 (noting that middle-class Blacks dominated the national civil rights movement and prevented lower-class Black spokespeople from emerging).

[6] See L.A. Ctr. for Community L. & Action, http://www.laccla.org/ (last visited Sept. 22, 2018).

[7] See Scott L. Cummings, Rethinking the Foundational Critiques of Lawyers in Social Movements, 85 Fordham L. Rev. 1987, 1990 (2017); Ashar, supra note 1, at 1904.

[8] In this article, lowercase “east” Los Angeles refers generally to the east side of the city, while capitalized “East” Los Angeles refers to the technical, unincorporated area of the county situated to the east of Boyle Heights.

[9] An example of this is the New Right movement of American conservatives in the late twentieth century. See Jack M. Balkin, How Social Movements Change (or Fail to Change) the Constitution: The Case of the New Departure, 39 Suffolk U. L. Rev. 27, 28 (2005) (explaining how the New Right emerged with the particular political objective of changing the existing legal interpretations of the U.S. Constitution). See generally Steven M. Teles, Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: the Battle for Control of the Law (2008) (tracking how twentieth-century American conservatives created institutions such as the Federalist Society and popularized ideologies like law-and-economics in order to assert influence on national law and policy).

[10] These are practices which would typically be illegal in municipal Los Angeles under the Los Angles Rent Stabilization Ordinance (RSO). See L.A. Mun. Code §§ 151.01 et seq. (prohibiting unauthorized rent increases and no-cause evictions).

[11] Narratives of Displacement and Resistance, Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (last visited Aug. 16, 2018), http://www.antievictionmappingproject.net/narratives.html.

[12] Josie Huang, Outside of LA, County Tenants Want Brakes on Rising Rents, KPCC (May 11, 2017), http://www.scpr.org/news/2017/05/11/71736/outside-of-la-county-tenants-want-brakes-on-rising/.

[13] Press Release, Office of Supervisor Hilda L. Solis, First Dist., County of Los Angeles, Supervisor Solis Leads Countywide Effort to Review Tenant Protections (May 16, 2017), http://hildalsolis.org/supervisor-solis-leads-countywide-effort-to-review-tenant-protections/.

[14] Sachi A. Hamai, Cty. of L.A., Report of the Tenant Protections Working Group (2018) (on file with author).

[15] Ashar, supra note 1, at 1895–98.

[16] Ruben Vives, As Rents Soar in L.A., Even Boyle Heights’ Mariachis Sing the Blues, L.A. Times (Sept. 9, 2017, 5:00 AM), http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-boyle-heights-musicians-gentrification-20170909-htmlstory.html.

[17] Elijah Chiland, Boyle Heights Mariachis Agree to 14 Percent Rent Hike but Win New Leases Ending Months-Long Strike, Curbed: L.A. (Feb. 16, 2018, 2:46 PM), https://la.curbed.com/2018/2/16/17018298/boyle-heights-mariachi-gentrification-rent-strike.

[18] Cummings & Eagly, supra note 1, at 490–513.

[19] Cummings, supra note 7, at 1993.

[20] Christian Monterrosa, Family on Rent Strike in Westlake Is Evicted After Not Paying Rent, Curbed: L.A. (Aug. 9, 2018, 11:10 AM), https://la.curbed.com/2018/8/9/17671478/rent-strike-westlake-eviction (quoting landlord as expressing concerns that eighty tenants who have gone on rent strike in mid-city Los Angeles “are getting bad and misleading advice from ‘tenant activists,’ who don’t understand rental contracts and property laws . . . .”); cf. Derrick A. Bell, Jr., Serving Two Masters: Integration Ideals and Client Interests in School Desegregation Litigation, 85 Yale L.J. 470, 476–77 (1976) (demonstrating that civil rights activists prioritized desegregation over improving school conditions).

[21] Cf. Cummings & Eagly, supra note 1, at 513 (explaining that public interest law firms often rely on attorney-client retainer agreements to navigate difficult ethical issues in movement representation).

[22] Kim TallBear, Standing With and Speaking as Faith: A Feminist Indigenous Approach to Inquiry, 10 J. Res. Prac. 1 (2014), http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/405/371.

[23] Narratives of Displacement and Resistance, supra note 11.

[24] Id.

[25] Eviction Lab, https://evictionlab.org (last visited Aug. 16, 2018).

[26] Aimee Inglis & Dean Preston, Tenants Together, California Evictions Are Fast and Frequent 8 (2018), https://actionnetwork.org/groups/tenants-together/files/23632/download.

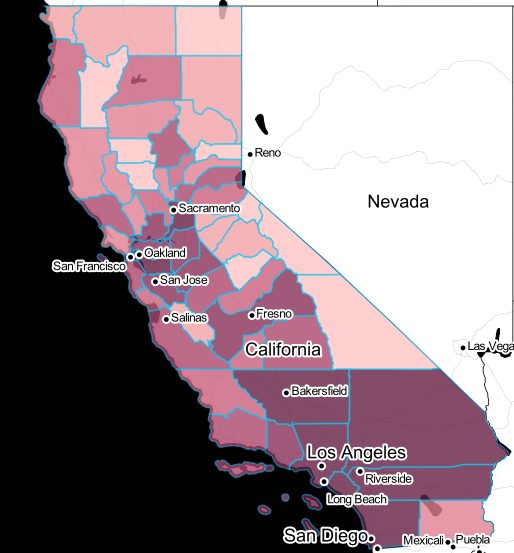

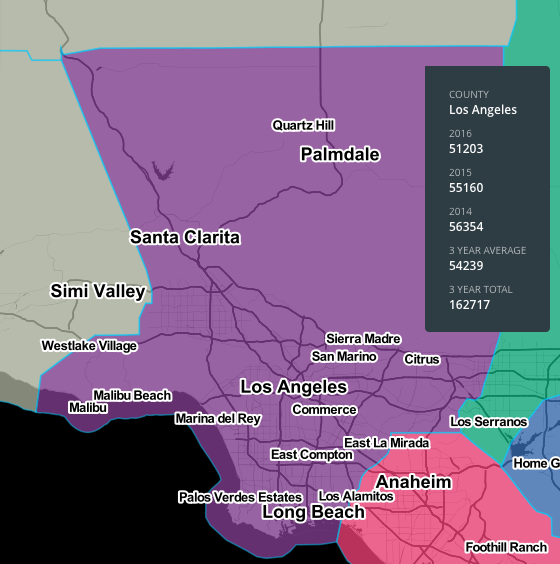

[27] This map shows court evictions per county across California from 2014 to 2016. Darker regions indicate a higher concentration of evictions. As shown in Figure 2, there were 162,717 unlawful detainers in Los Angeles County during this time. AEMP and Tenants Together obtained this previously unreleased data in early 2018 from the State Judicial Council, which tracks court evictions statewide. See the interactive map at Unlawful Detainer Evictions in California, 2014–2016, Anti-Eviction Mapping Project & Tenants Together, https://www.antievictionmap.com/uds-in-ca/ (last visited Sept. 13, 2018).

[28] Eviction Def. Collaborative, Eviction Report 2015 5 (2016), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/52b7d7a6e4b0b3e376ac8ea2/t/5b1276fc8a922da05029225d/1527936777268/EDC_2015.pdf.

[29] Loss of Black Population, Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, http://www.antievictionmappingproject.net/black.html (last visited Aug. 16, 2018).

[30] Bell, supra note 20, at 476–77, 515–16 (noting that civil rights leaders prioritized desegregation over improving school conditions).

[31] See Monterrosa, supra note 20 (quoting a landlord as expressing concerns that 80 tenants who have gone on rent strike in mid-city Los Angeles “are getting bad and misleading advice from ‘tenant activists,’ who don’t understand rental contracts and property laws”); Know Your Rights, Councilmember Mitch O'Farrell News (Office of Councilmember Mitch O’Farrell, 13th Dist., Los Angeles, Cal.), https://mailchi.mp/lacity/know-your-rights?e=5fcf622ad2 (August 11, 2018) (explaining to his subscribers that the Los Angeles Tenants Union’s call for a rent strike is “bad advice” that will lead the tenants to be evicted).

[32] See Greta Kaul, Evictions, on the Rise Nationwide, Don’t Affect All Parts of Minneapolis Equally, MinnPost (Oct. 25, 2017),

https://www.minnpost.com/politics-policy/2017/10/evictions-rise-nationwide-don-t-affect-all-parts-minneapolis-equally (reporting on a speaking event in which a Princeton University professor noted that research on the effects of rent control was inconclusive).

[33] See Rebecca Diamond, Tim McQuade & Franklin Qian, The Effects of Rent Control Expansion on Tenants, Landlords, and Inequality: Evidence from San Francisco 3–5 (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Research, Working Paper No. 24181, 2018).

[34] See, e.g., Richard P. Appelbaum et al., Scapegoating Rent Control: Masking the Causes of Homelessness, 57 J. Am. Plan. Ass’n 153, 155–156 (refuting common critiques of rent control in economics and urban policy fields by citing evidence from studies conducted in cities with rent control); Inglis & Preston, supra note 26, at 12–13 (showing how rent control is an important component of eviction defense in California); John Ingram Gilderbloom, Moderate Rent Control: Its Impacts on the Quality and Quantity of the Housing Stock, 17 Urb. Aff. Q. 123 (1981) (noting that “moderate rent control” does not negatively impact housing construction and habitability when compared to cities without rent control); Joan Ling & Doug Smith, Eviction Crisis in California Requires Legal Remedy, S.F. Chron. (July 20, 2018, 10:34 PM), https://www.sfchronicle.com/opinion/article/Eviction-crisis-in-California-requires-legal-13092911.php (elaborating how rent control can help mitigate the eviction crisis, nationwide and in California); Miriam Zuk, Rent Control: The Key to Neighborhood Stabilization?, Haas Inst. Blog (Sept. 9, 2015), https://haasinstitute.berkeley.edu/rent-control-key-neighborhood-stabilization (noting that rent control can limit displacement and increase housing stability in urban areas).

[35] See Leslie Gordon, Urban Habitat, Strengthening Communities Through Rent Control and Just-Cause Evictions: Case Studies From Berkeley, Santa Monica, and Richmond 11–12 (2018), http://urbanhabitat.org/sites/default/files/UH%202018%20Strengthening%20Communities%20Through%20Rent%20Control_0.pdf (analyzing Berkeley and Santa Monica).

[36] See Allan David Heskin, Tenants and the American Dream: Ideology and the Tenant Movement 39–66 (1983) (chronicling the histories and legacies of tenants’ rights movements in California).